Thiemt, Britta (2020) Qualitative insights into pregabalin use among individuals in opioid agonist treatment. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 74, Summer 2020, pp. 12-14.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 74)

1MB |

Recent research and reports have highlighted the drug pregabalin due to its potential for dependence and abuse, and an increase in pregabalin-related overdose deaths in several European countries. As a prescription-only central nervous system (CNS) depressant analogue to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), it is used for an array of conditions, including neuropathic pain, epilepsy, generalised anxiety disorder, and fibromyalgia.1 In a 2020 study published in Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems, Brennan and Van Hout present qualitative insights into the experiences of patients in opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with pregabalin.2 The authors selected OAT patients as their study population because of their increased risk for problematic use of pregabalin and overdose.3 Though related research in Ireland is sparse, international evidence has demonstrated that using pregabalin leads to the development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms when ceased. The combined use of both opiates and pregabalin as two CNS depressants, while highly prevalent, has been shown to increase the risk of overdose and death.4 The current study was the first in Ireland to capture the experiences of OAT patients using pregabalin.

Methods

The qualitative descriptive study utilised one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Participants were recruited from a service offering OAT and harm reduction in Dublin. To be eligible, participants had to be both current or former OAT patients and current or recent users of pregabalin. Of 15 participants, nine were male and six female, ranging in age from 25 to 45 years. Data were analysed using thematic analysis assisted by NVivo 12 software. Having finalised the thematic framework, one researcher performed a participant check to ensure the accurate reflection of participants’ views.

Key findings

Use patterns: One-half of participants were initially prescribed pregabalin, predominantly for pain. The others first consumed pregabalin after receiving it from peers. For many participants, being part of a polydrug use/‘tablet taking’ culture and a history of using benzodiazepines or Z-drugs often preceded pregabalin use. Participants recounted combining pregabalin with substances such as methadone, benzodiazepines, and Z-drugs, and with stimulants such as crack cocaine to ‘come down’. Many stated consuming more than 1000 mg daily, with doses ranging from 800 mg to 6000 mg. Most took pregabalin orally, but none reported injecting, given its connotation with past heroin use.

Motivators: The reasons for consuming pregabalin included the self-regulation of negative emotions and enhancement of sociability and confidence. Participants specifically stated using pregabalin to numb distress and underlying psychological issues such as trauma.

Side-effects: Examples of undesirable side-effects mentioned were losing consciousness or control and behaviours such as shoplifting or aggression due to feeling ‘invincible’.

Sourcing routes: Strategies included approaching multiple doctors, exaggerating symptoms while seeking prescriptions, buying street pregabalin (also through social media), or diverting legitimate prescriptions from their network.

Role of medical professionals: While some described doctors as gatekeepers to sourcing pregabalin, multiple participants received it from doctors or pharmacists illegitimately, filling prescriptions early or selling prescriptions.

Detoxification and withdrawal symptoms: One participant recounted experiencing very severe physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms while detoxing from pregabalin at home. Another reported undergoing a medically supervised detox. Several other participants described psychotic symptoms and suicidal ideation during pregabalin withdrawal consistent with previous descriptions in the literature.

Combination with opioids: The data provided some insights into the popularity of combining opioids with pregabalin. Participants reported using it to manage withdrawal symptoms from opioids and finding it superior to other substances. Use of pregabalin was also explained with its similarity in effect to opioids, specifically heroin. Additionally, pregabalin was described as strong in its effect, and therefore attractive to those with built-up tolerance.

Harm perception and reduction: Participants were alert to the risk of overdose, often due to personal experiences, and reported using indigenous harm reduction strategies, such as decreasing consumption and not buying counterfeit Lyrica.

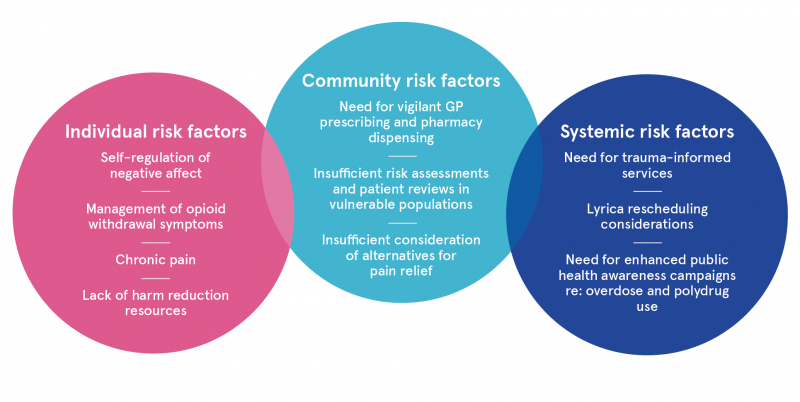

Figure 1: Risk factors for problematic pregabalin use in an OAT patient sample in Dublin

Discussion

Based on the participant responses, Brennan and Van Hout conceptualise the consumption of pregabalin among service users receiving OAT within a socio-ecological model, reflecting interacting risk factors on the individual, community, and systemic levels (see Figure 1). They extrapolate several recommendations for policy and healthcare service delivery from participants’ accounts.

Given the participants’ worrying descriptions of malpractice, Brennan and Van Hout emphasise the need for monitoring pregabalin prescriptions and for doctors and pharmacists to carry out risk assessments considering OAT patients’ vulnerability to pregabalin dependence, reduce off-label prescribing, and choose alternatives to pregabalin for pain relief.

The authors also call for increased healthcare support for OAT patients using pregabalin, such as trauma-informed interventions, medical supervision, and vigilance to psychiatric symptoms during pregabalin detox, harm reduction measures, and information campaigns.

The study’s findings should be viewed in light of several methodological limitations, including the small sample, single study location, and potential recall bias. Considering the prevalence of polydrug use, statements about the effects of pregabalin should be interpreted with caution.

The study nonetheless provides important first insights into the risk factors for pregabalin use among OAT patients as an at-risk group, and features recommendations for policy and health service responses grounded in qualitative data.

1 Lyons S (2018) Overview on pregabalin and gabapentin. Drugnet Ireland, 65(1): 11–12. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/29105/

2 Brennan R and Van Hout MC (2020) ‘Bursting the Lyrica bubble’: experiences of pregabalin use in individuals accessing opioid agonist treatment in Dublin, Ireland. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems, 22. Early online.

https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31533/

3 McNamara S, Stokes S, Kilduff R and Shine A (2015) Pregabalin abuse amongst opioid substitution treatment patients. Irish Medical Journal, 108(10): 309–310. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/24965/

4 Al-Husseini A, Van Hout MC and Wazaify M (2018) Pregabalin misuse and abuse: a scoping review of extant literature. Journal of Drug Issues, 48(3): 356–376.

A Substance use and dependence > Personal history of substance use (pathway) > Tolerance

B Substances > Opioids (opiates)

B Substances > New (novel) psychoactive substances > Other novel substances > Gabapentinoids GABA (Pregabalin / Gabapentin)

F Concepts in psychology > Motivation

HJ Treatment or recovery method > Substance disorder treatment method > Substance replacement method (substitution) > Opioid agonist treatment (methadone maintenance / buprenorphine)

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Risk and protective factors > Risk factors

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Treatment and maintenance > Treatment issues (pain management)

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page