Dillon, Lucy (2020) LSE report on Irish response to Covid-19. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 75, Autumn 2020, pp. 9-10.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet 75)

590kB |

In July 2020, the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) published a report on Ireland’s response to Covid-19 in relation to people who are homeless and use drugs, entitled Saving lives in the time of COVID-19: case study of harm reduction, homelessness and drug use in Dublin, Ireland.1 The report is a policy briefing that outlines the policy changes made in Ireland to harm reduction services in response to Covid-19. It argues that lives within the target group were saved as a result of these changes and that the policy changes should be maintained in the post-Covid era.

Housing response

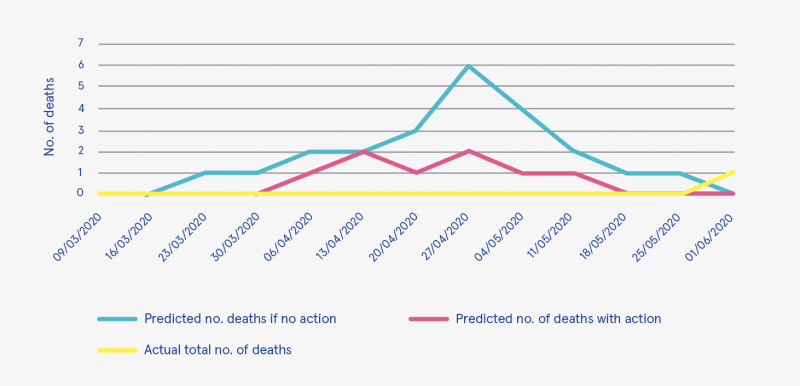

People experiencing homelessness were identified as a vulnerable group when the Covid-19 pandemic reached Dublin. Protocols for identification and immediate testing for people in this group were developed and implemented. Accommodation was provided to allow suspected and positive cases to isolate, as well as those deemed vulnerable due to age or medical condition. The report argues that this resulted in much lower than expected Covid-19 infection and mortality rates. Seven hundred and fifty clients were tested, of whom 63 tested positive. One person died. Dr Austin Carroll is one author of the report and the Covid-19 clinical lead for homelessness in Dublin. His team carried out projections on the number of expected fatalities using a data projection programme developed in the United Kingdom and adjusted for Ireland.2 It indicates that the policy response, combined with the quick and dedicated response of services and their staff, contributed to a much lower than expected mortality figure (see Figure 1).

Drug policy changes

In addition to meeting the testing and housing needs of this group, policy changes were made that improved access to three harm reduction interventions for those who were using drugs. These were opiate substitution therapy (OST); naloxone; and benzodiazepine (BZD) maintenance, which are outlined below.

Opiate substitution therapy: There were two key changes in the area of OST – one related to accessing a programme, the other to the dispensing of methadone. National contingency guidelines were issued, allowing for reduced waiting times and removal of caps on recruitment to OST at the two clinics that provide treatment for this group (National Drug Treatment Centre and GMQ Medical).3 These new guidelines resulted in the waiting times for treatment at one service provider (GMQ Medical) being reduced from 12–14 weeks to 2–3 days. Access was further improved by other treatment clinics agreeing to take on homeless patients who were resident in their catchment areas. Supervision guidelines were also amended. Staff at relevant agencies were allowed to collect clients’ OST medications and deliver them to the client’s accommodation. This supported clients who were self-isolating.

Naloxone: Access pathways to the opioid antagonist naloxone were relaxed in response to the Covid-19 crisis through the national contingency guidelines.3 The new guidelines recommend that everyone in receipt of OST should be offered and encouraged to take a supply of naloxone. It was to be administered by a person trained in its use and the injectable product used instead of the intranasal product. Access was then extended to those most at risk of overdose in the evolving situation, and packs were distributed to those using a needle and syringe programme by Ana Liffey Drug Project. The requirement for a prescription to be issued by a general practitioner to the client by name could be met retrospectively.

Figure 1: Mortality from Covid-19 homeless sector

Source: Carroll et al. (2020), p. 4

Benzodiazepine maintenance: In Ireland, the focus of national guidelines for the treatment of BZD use is detoxification, not maintenance.4 However, in response to the pandemic, national contingency guidelines were published, which recommended that isolating clients of treatment services could be offered up to 30 mg daily to prevent withdrawals for the period of isolation. O’Carroll et al. note that this was extended by those working in the homeless sector to those who were shielding (p. 7) and to all those on OST with established BZD dependency in one service (GMQ Medical). As with OST medications, service providers were able to deliver medications to clients in their accommodation.

Call to sustain the changes

In their conclusion, the authors note that the key element of the first two of these policy changes (the removal of barriers to rapid access to OST and naloxone) resulted in the implementation of existing national policy, which they argue raises the question as to why barriers existed prior to the pandemic. They also argue that prior to and independent of Covid-19 there was a ‘strong public health argument for having no waiting lists for OST and improved naloxone distribution to PWUD [people who use drugs]’ (p. 9).

The authors describe the pandemic as having ‘acted as a catalyst for changes in the delivery of harm reduction measures to homeless PWUD’ (p. 10). They recommend that ‘practices continue to deliver on OST and naloxone policy objectives and that policy makers review the evidence on BZD maintenance treatment’ (p. 10). In conclusion, they view the Covid-19 experience as a ‘potentially important milestone in the development of national drug policies’ (p. 10).

Conclusion

As mentioned, the report’s authors recommend that the policy changes made in response to Covid-19 be maintained in the post-Covid era. While there is no reference to BZD use, the June 2020 Programme for Government: our shared future5 offers a commitment to elements of the other two policy changes:

- To retain the specific actions taken to support increased and improved access to opioid substitution services during Covid-19,

so that pre Covid waiting times in accessing these services are reduced. - To support the rollout of access to and training in opioid antidotes.

1 O’Carroll A, Duffin T and Collins J (2020) Saving lives in the time of COVID-19: case study of harm reduction, homelessness and drug use in Dublin, Ireland. London: London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/32291/

2 The data projection programme was devised for the homeless population in London by Prof Al Story and Prof Andrew Hayward of University College London.

3 Health Service Executive (HSE) National Social Inclusion Office (2020) Guidance on contingency planning for people who use drugs and COVID-19. Dublin: HSE.

https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31804/

4 Health Service Executive (2016) Clinical guidelines for opioid substitution therapy. Dublin: HSE. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/26573/

5 Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Green Party (2020) Programme for Government: our shared future. Dublin: Department of the Taoiseach. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/32212/

B Substances > New (novel) psychoactive substances > Benzodiazepines

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Communicable / infectious disease > Viral disease / infection > Coronavirus (COVID-19)

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Harm reduction > Substance use harm reduction

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Health care delivery

MA-ML Social science, culture and community > Social condition > Homelessness > Homeless services

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Policy > Policy on substance use > Harm reduction policy

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page