Dillon, Lucy (2019) Addressing educational disadvantage – Youthreach and DEIS. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 71, Autumn 2019, pp. 25-27.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet 71)

1MB |

Educational disadvantage is widely recognised as a risk factor for substance misuse.1 Improving supports for young people at risk of early substance use is an action of the national drugs strategy – Reducing harm, supporting recovery: a health-led response to drug and alcohol use in Ireland 2017-2025 (Action 1.2.5),2 which identifies the preventative role of programmes that support young people to stay in education. The Government funds several programmes in this area and two of its key programmes have recently been evaluated:

Youthreach: Evaluation of the National Youthreach Programme1

Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS): The evaluation of DEIS at post-primary level: closing the achievement and attainment gaps.3

PROGRAMME 1: Youthreach

Youthreach is the Irish Government’s primary response to early school-leaving. It aims ‘to provide early school leavers (16–20 years) with the knowledge, skills and confidence required to participate fully in society and progress to further education, training and employment’ (p. 9).4 It is described as not only having a focus on progression to education and training but also plays a role in facilitating social inclusion (p. xi).1 The programme has been the subject of an in-depth evaluation, whose findings were published in June 2019 in Evaluation of the National Youthreach Programme.1

Youthreach provides what is described as ‘second-chance education’ for those who have left mainstream second-level school before Leaving Certificate level (p. xi). It is delivered in two settings that have their own distinct governance and funding structures: Youthreach centres, of which there are 112 nationally; and Community Training Centres, of which there are 35 nationally. Centres vary in what they offer learners. While QQI Levels 3 and 4 are the most common courses offered, some provide Level 2 courses and the Leaving Certificate Applied programme. A small number offer the Junior Certificate and the Leaving Certificate. In 2017, some 11,104 learners took part in the programme (p. xi).

Methods

The evaluation takes a mixed methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data gathered from a range of stakeholders. This approach enables the evaluators to assess the programme’s effectiveness and reflect the multiple challenges being faced by young people involved with the programme, for example, socioeconomic disadvantage and special educational needs. Furthermore, the approach captures the range of outcomes being achieved by a programme which promotes the development of a broad set of skills among young people, with an emphasis on personal and social development.

The evaluation team carried out surveys of senior managers at Education and Training Board level, centre coordinators and managers; and in-depth case studies of 10 centres, which involved qualitative interviews with staff, coordinators/managers, and current and former learners. They emphasise the importance of capturing young people’s voices through the evaluation; they describe the interviews with young people as having yielded new insights into their pathways into the programme, their experiences of Youthreach, and the impact they feel it has had on them.

Selection of findings

The report is highly detailed and explores all aspects of the programme, including the profile of learners; referral to the programme; governance and reporting structures; programme funding and resources; curriculum; approaches to teaching and learning; and learner experiences and outcomes. It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed description of the full range of findings; however, a selection of key findings is provided here.

Increased marginalisation

While there has been a notable decline in the number of early school-leavers in Ireland since 2009, this group was found to have become ‘more marginalised in profile’ (p. 205) over time. What is described as a ‘striking finding’ (p. 205) is that young people are presenting to Youthreach with greater levels of need, with increased prevalence of mental health and emotional problems as well as learning difficulties. Among the challenges faced was substance misuse – both that of young people themselves and that of a family member. This concentration of complex needs was found to have implications for the kind of support required by learners and the staff skill set necessary to meet these needs.

Programme aims and outcome measurements

Senior managers and coordinators adopted a holistic view of the programme aims. While there was some variation between groups of stakeholders, overall they perceived the programme as having multiple aims, including re-engaging young people in learning; providing a positive learning experience; fostering the development of personal and social skills, the acquisition of qualifications, and progression to education, training and employment. Given this broad perspective, they were largely critical of the current system in which the programme’s metrics only capture the aims of the programme in terms of progression to education, training, and employment.

Course content and learning

As mentioned above, centres varied in the courses and qualifications they offered. While this was in part attributed to governance structures, the findings overall indicated that centres tailored provision to learner needs. As well as accredited courses provided by Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) and the State Examinations Commission, the vast majority also offered other activities to meet the needs of their learners. Among these were ‘courses and talks around drug awareness’ (p. 209). Overall, learners were very positive about their Youthreach learning experiences, especially when compared with their experience of mainstream education.

Additional supports

Given the needs profile of Youthreach learners, providers offered a range of other supports for learners. These included work placement, career guidance, personal counselling, and informal support from staff. The evaluation found that central to this was the quality of relationships with staff and other young people. Learners reported that the support, respect, and care they received from centre staff were critical.

Outcomes

Evidence on outcomes was reported through the routine monitoring system for Youthreach (SOLAS FARR database), the study surveys, and qualitative interviews. Findings from the quantitative indicators of outcomes included that, for 2017, the SOLAS FARR database indicated non-completion rates of 14% across the programme; for the same year, the accreditation rate for both full and component awards was 42%. When comparing the number of awards with the number of learners (using survey data from coordinators and managers), an estimated 60% of those completing the programme received a full award. Also, according to the survey data, 45% of completers progress on to another education or training course; 43% go straight into the labour market; and one in six completers are unemployed (pp. 211–12).

Positive outcomes related to the development of personal and social skills as well as enhancement of emotional wellbeing were also reported. For example, learners identified improvements in their engagement with learning, increased self-confidence, and the development of ‘a purpose in life and hope for the future’ (p. 212). As mentioned above, there was heavy criticism of these outcomes not being captured through routine monitoring systems.

Conclusion

Overall, the study findings indicate that the programme works well as second-chance provision for often vulnerable young people with complex needs.

[It offers a] positive experience of teaching and learning, fostering personal and social skill development, and equipping many with certification to access further education, training and employment options …. providing courses and approaches tailored to their needs, and embedding education/training provision within a broader network of supports. (p. xvii)

PROGRAMME 2: DEIS

Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) is the Department of Education and Skills’ policy instrument to address educational disadvantage, which was launched in 2005. It aims to improve attendance, participation, and retention in designated schools located in disadvantaged areas. A range of supports is provided to participating schools; for example, a lower pupil–teacher ratio in some schools; access to the Home School Community Liaison Scheme; the School Meals Programme; and literacy and numeracy supports.

The programme has been the subject of a number of reports, the most recent of which is The evaluation of DEIS at post-primary level: closing the achievement and attainment gaps, published in late 2018 by the Educational Research Centre.3 The report looks at achievement and retention in DEIS and non-DEIS schools at post-primary level.

Key findings

Overall achievement

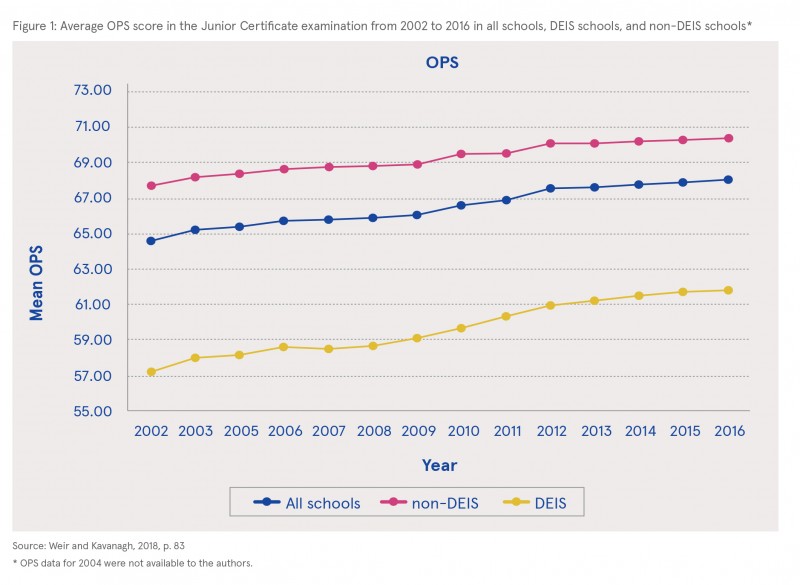

Between 2002 and 2016, there was a narrowing of the gap in Junior Certificate examination (JCE) achievement between DEIS and non-DEIS schools, as measured by the overall performance scale (OPS).5 The average annual rate of increase in non-DEIS schools from 2002 to 2016 was 0.19 OPS points, but was significantly higher (p<0.001) for DEIS schools, at an average increase of 0.33 OPS points per year (see Figure 1). What this means in terms of grades (A–E) is that DEIS schools saw an increase over the period that was equivalent to an approximate increase of one letter grade. A similar increase was not found in non-DEIS schools. The overall gap in OPS reduced from 10.5 points in 2002 to 4.6 in 2016. When looking at two specific subjects, a narrowing of the gap was also found for English and mathematics.

Retention

The study found a significant upward trend in both Junior Cycle and Senior Cycle retention for the entry cohorts between 1995 and 2011 across all schools. Those entering 1st Year in 1995 had a Junior Cycle retention rate of 94.3%, which had increased to 97.1% for the 2011 cohort. For the same period, the Senior Cycle retention rate increased from 77.3% to 90.2%. Despite a narrowing of the gap, there continues to be sizeable gaps in retention between DEIS and non-DEIS schools in both cycles. For the 1995 cohort, there was an 8.6 percentage point gap for Junior Cycle, which had reduced to 2.2 percentage points for the 2011 cohort. For Senior Cycle, there was a 22.1 percentage point gap for the 1995 cohort; for the most recent cohort, it was 11 percentage points.

Medical card possession and achievement

In both DEIS and non-DEIS schools, gaps existed between the average achievements of students from medical card-holding families and those from families without medical cards; those without medical cards outperformed those with medical cards.

Social context effect

The authors explored whether there was a ‘social context effect’ on student achievement. They tested the hypothesis that increasing concentrations of students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds would have a negative impact on individual student achievement, irrespective of that individual’s own socioeconomic background. The two student-level variables on which data were available – gender and medical card possession – explained 31% of the between-school variance in English and mathematics achievement in 2016. The addition of the measure of social context, that is, the percentage of students from medical card-holding families in a school, explained an additional 40% of the between-school variance in English achievement and an additional 42% of the between-school variance in mathematics achievement in 2016. This indicates a clear social context effect – the impact of being a student in a school with concentrations of other socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds has a substantial negative impact on achievement, regardless of whether a student has a medical card themselves or not.

Final comment

The report is descriptive of changes over time and illustrates a narrowing of the gap between DEIS and non-DEIS schools. As suggested by the authors, the findings on medical cards and the social context effect suggest support for policies that target resources at schools with concentrations of students from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds. However, the report is limited in its inability to conclude whether or not the changes found are attributable to the DEIS programme. As with previous DEIS reports, a key limitation is that a control group is not used; therefore, it cannot be established with any certainty whether improvements are due to the programme or to improvements that would have happened anyway.

1 Smyth E, Banks J, O’Sullivan J, McCoy S, Redmond P and McGuinness S (2019) Evaluation of the National Youthreach Programme. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/30687/

2 Department of Health (2017) Reducing harm, supporting recovery: a health-led response to drug and alcohol use in Ireland 2017-2025. Dublin: Department of Health. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/27603/

3 Weir S and Kavanagh L (2018) The evaluation of DEIS at post-primary level: closing the achievement and attainment gaps. Dublin: Educational Research Centre. Available online at:

4 Department of Education and Skills (DES) (2015) Operator guidelines for the Youthreach programme. Dublin: DES.

5 OPS is a tool in which a numerical value is attached to each of the alphabetical grades (A–E) awarded to JCE candidates for each subject; summing these values produces an index of a candidate’s general scholastic achievement across their seven best subjects. These are then aggregated to produce an index of achievement in the JCE at a school level.

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Prevention by setting > Youth project / club based prevention

L Social psychology and related concepts > Interpersonal interaction and group dynamics > Social support

L Social psychology and related concepts > Social inclusion and exclusion

N Communication, information and education > Educational environment / institution (school / college / university)

T Demographic characteristics > Adolescent / youth (teenager / young person)

T Demographic characteristics > Early school Leaver

T Demographic characteristics > Teacher / lecturer / educator

T Demographic characteristics > Prevention / youth worker

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page