Lynn, Ena (2019) Has an increase in the dispensing of pregabalin influenced poisoning deaths in Ireland? Drugnet Ireland, Issue 71, Autumn 2019, pp. 15-17.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet 71)

1MB |

Introduction

Deaths caused by the toxic effect of drugs (poisoning deaths) are preventable and good clinical practice with supporting legislation can help prevent such deaths. Irish data on poisoning deaths show an increase in direct pregabalin-related poisoning deaths from the years 2013 to 2016.1 Of note, pregabalin – a prescribed medicine used in the treatment of several medical conditions, including epilepsy, neuropathic pain, and generalised anxiety disorder – has only been included in the routine postmortem toxicology screen by the State Laboratory since 2013.

Following the introduction of pregabalin in 2004, international evidence found an increase in its prescription rates.2,3,4 Fatal overdoses related to pregabalin have been reported and are almost always in combination with other drugs.5,6 The aim of this study was to examine whether or not the increase in the dispensing of pregabalin has impacted on poisoning deaths in Ireland between 2013 and 2016.

Methods

Prescription data were retrieved from the Health Service Executive (HSE) Primary Care Reimbursement Service (PCRS) annual reports,7 which record payment and prescription frequency for several services in Ireland. These services include the General Medical Services (GMS), which in 2014 related to 43% of the general population,8 and services that cover the remainder of the population; data on drugs provided through the Long-Term Illness Scheme (LTI), which covers free drugs for the treatment of specific long-term illnesses; and data on repayments through the Drugs Payment Scheme (DPS), which reimburses any citizen who pays more than a set amount monthly for medicines.

Data on all poisoning deaths for the years of death 2013–2016 with positive toxicology for pregabalin were extracted from the National Drug-Related Deaths Index (NDRDI). The NDRDI is an epidemiological census which records all poisoning deaths by drug(s) and/or alcohol. It also records non-poisonings deaths among persons who have a history of drug and/or alcohol dependence or misuse of drugs. The NDRDI’s main data source is coronial files. All postmortem toxicological analyses included in this report were performed by the State Laboratory in Ireland. Further details on the NDRDI methodology can be found in a previous Health Research Board publication.9

Descriptive statistics are presented for the number of dispensings and deaths over time. In addition, correlational analysis using linear regression was applied to estimate the relationship between number of dispensings for pregabalin and deaths over the reported time period.

Results

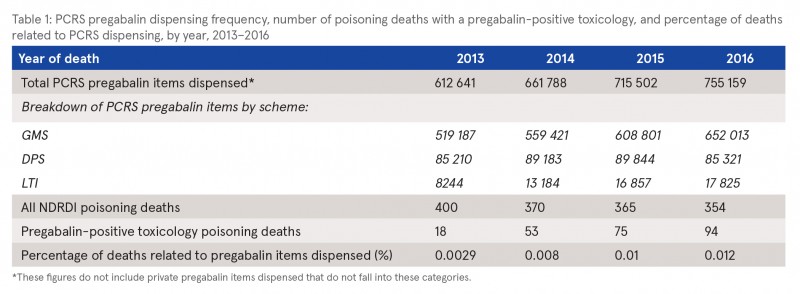

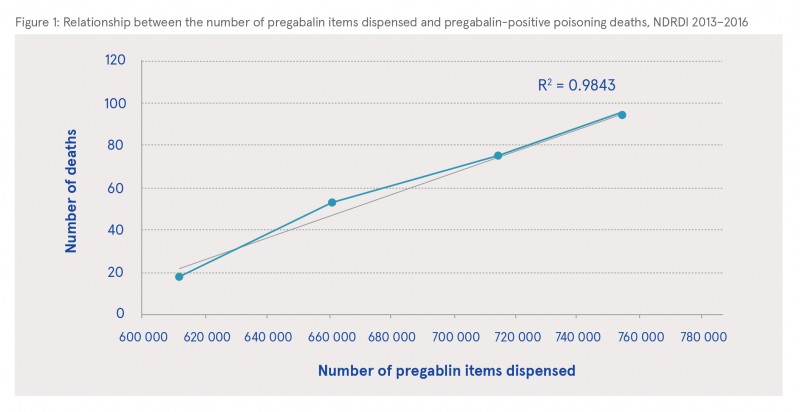

For the years of death 2013–2016 inclusive, the NDRDI recorded a total of 1489 poisoning deaths. Pregabalin was present on toxicology reports of 240 (16%) poisoning deaths during this period, increasing from 18 (4.5%) in 2013 to 94 (26%) in 2016, indicating an upward trend (χ2 = 74.626, p=<0.001) in the presence of pregabalin in poisoning deaths (see Table 1). The numbers of dispensed pregabalin items are shown in Table 1; these numbers increased year on year. Figure 1 shows a strong positive correlation between the number of pregabalin items dispensed through the HSE PCRS scheme and the number of poisoning deaths where pregabalin was present on toxicology reports over time, with a coefficient (R2) value of 0.9843.

Discussion

This ecological study shows that pregabalin-positive poisoning deaths are increasing in line with the increased dispensing of pregabalin in Ireland. In the United States, it has been suggested that the increase in prescribing pregabalin is related to clinicians using it outside its licensed indicated use, as an alternative to opioids for a variety of pain management.2 Since April 2019, in the United Kingdom, following recommendations from the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs,10 pregabalin (and gabapentin) has been classified as a Class C drug. This means that pregabalin cannot be repeat-dispensed and prescriptions will only be valid for one month. Despite the acknowledgement that this will incur extra work for doctors, pharmacists, and especially patients, the medical profession in general supports this change.11 Results from our study support the consideration of similar reclassification of pregabalin in Ireland. In Ireland, the HSE issued correspondence in June 2016 in relation to the dangers associated with prescribing pregabalin;12 however, this needs to be supported with tighter controls through legislative changes.

1 Health Research Board (2019) National Drug-Related Deaths Index: 2004 to 2016 data. Dublin: Health Research Board. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/30174/

2 Goodman CW and Brett AS (2017) Gabapentin and pregabalin for pain – is increased prescribing a cause for concern? New Engl J Med, 377(5): 411–14.

3 Spence D (2013) Bad medicine: gabapenin and pregabalin. BMJ, 347(f6747): 1–2.

4 Schwan S, Sundström A, Stjernberg E, Hallberg E and Hallberg P (2010) A signal for an abuse liability for pregabalin – results from the Swedish spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting system. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 66(9): 947–53.

5 Bonnet U and Scherbaum N (2017) How addictive are gabapentin and pregabalin? A systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 27(12): 1185–1215.

6 Lyndon A, Audrey S, Wells C, Burnell ES, Ingle S, Hill R, et al. (2017) Risk to heroin users of polydrug use of pregabalin or gabapentin. Addiction, 112(9): 1580–89.

7 Health Service Executive (2019) Primary Care Reimbursement Service: Statistical analysis of claims and payments: 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016. Annual reports. Dublin: Health Service Executive. Available online at: https://www.sspcrs.ie/portal/annual-reporting/report/annual [Accessed 25 March 2019] (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/778sdEdZE).

8 Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service (IGEES) (2017) General Medical Services Scheme: Staff paper 2016. Dublin: Department of Public Expenditure and Reform. [Available online at: http://www.budget.gov.ie/Budgets/2017/Documents/3.%20General%20Medical%20Services%20Scheme.pdf [Accessed 25 March 2019] (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/778toW8jG)

9 Lynn E, Lyons S, Walsh S and Long J (2009) Trends in deaths among drug users in Ireland from traumatic and medical causes, 1998 to 2005. Dublin: Health Research Board. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/12645/

10 Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (2016) Letter to the Minister for Preventing Abuse and Exploitation re pregabalin and gabapentin advice. London: Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/491854/ACMD_Advice_-_Pregabalin_and_gabapentin.pdf [Accessed 25 March 2019].

11 Torjesen I (2019) Pregabalin and gabapentin: what impact will reclassification have on doctors and patients? BMJ, 364: l1107.

12 Health Service Executive (2016) Medicines Management Programmes (MMP): Preferred drug initiative. Circular 046/16. Dublin: Health Service Executive. Available online at: https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/pcrs/circulars/gp/preferred%20drugs%20programme.pdf [Accessed 25 March 2019] (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/778ruH8II).

B Substances > New (novel) psychoactive substances > Other novel substances > Gabapentinoids GABA (Pregabalin / Gabapentin)

E Concepts in biomedical areas > Medical substance > Prescription drug (medicine / medication)

G Health and disease > Substance use disorder (addiction) > Drug use disorder > Drug intoxication > Poisoning (overdose)

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Patient / client care management

P Demography, epidemiology, and history > Population dynamics > Substance related mortality / death

T Demographic characteristics > Doctor / physician

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page