Dillon, Lucy (2022) The cannabis policy debate. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 82, Summer 2022, pp. 5-7.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 82)

661kB |

Cannabis for non-medical use (recreational use) is the subject of increasing policy debate across Europe. This debate reflects the complexity of the decisions to be made by policymakers and other stakeholders. While the penalties for using or possessing small amounts of cannabis for recreational use have been reduced in several European countries, recent developments in Luxembourg, Malta, and Germany suggest a more significant shift in policy trends in Europe (see Box 1).

To support an evidence-based debate and policy development process, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) has produced a series of outputs on the topic. This article focuses on two of these outputs. First, a report on the experiences of the Americas in implementing policy change – Monitoring and evaluating changes in cannabis policies: insights from the Americas – and, second, discussions from a webinar held on Cannabis Control Approaches across Europe in October 2021.1,2

It should be noted that this article is focused on cannabis for recreational use and not use for medical reasons or use as an ingredient in other products such as food or cosmetics. However, it is acknowledged that the new forms and emerging uses bring a complex set of challenges for European policy in this field.

Context – a more tolerant policy environment

The broader drug policy context is important when considering the changes in policy on recreational cannabis use. Support has been growing internationally for a move towards a more human rights and health-led approach to drug policy, away from the ‘war on drugs’ rhetoric of the more criminal-led approach. This is evident in key policy documents, including the European Union (EU) drugs strategy (2021–2025) and the outcome document of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly Special Session 2016.3,4 The harms caused by the prohibitionist approach to cannabis are well documented, as is its failure to reduce the prevalence of cannabis use. This has created a political environment which is increasingly accepting of adopting a less penalising model. This can take many forms along a continuum that includes depenalisation, decriminalisation, regulation, and legalisation.5

Developments in the Americas

The 2010s have seen the production and sale of cannabis for recreational use to adults legalised in Uruguay in 2013, Canada in 2018, and 18 states of the United States of America (USA), starting in 2012. Far from a homogenous shift in policy, the experience in the Americas has illustrated some of the wide variety of regulatory models that can be adopted and the complex nature of this policy debate. In January 2020, the EMCDDA published a technical report on Monitoring and evaluating changes in cannabis policies: insights from the Americas, as noted earlier.1 The aim was to review the changes governing recreational cannabis policies in the Americas and the findings of any preliminary evaluations.

Implementing regulation in the Americas

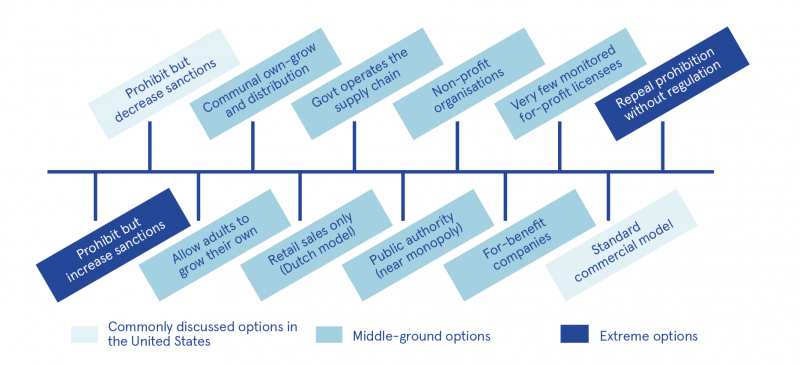

The report highlights the heterogeneity in approaches adopted across the jurisdictions. Figure 1 (p. 13)1 is used in the report to illustrate some of the alternatives to the status quo of prohibition of cannabis supply. While not the only option adopted in the US, the for-profit commercial model is common. However, Uruguay and Canada have adopted more restrictive models. They have created regulatory regimes with an intention to limit the power of private businesses in the market. Uruguay was the first country to operate a state-run dispensary system. The authors note that the options in Figure 1 are not mutually exclusive. For example, most jurisdictions allow both home production and commercial sales of cannabis. The overall message from this part of the report was that the motivations driving the policy change, the legislative frameworks, and the models implemented are varied and comparing their implementation and impact is complex.

Source: EMCDDA (2020),1 Figure 3.1, p. 13. Originally sourced from JP Caulkins et al. (2015) Considering marijuana legalization. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Figure 1: Some alternatives to status quo cannabis supply prohibition

Impact of regulation

In the report, a literature review was carried out of studies that would provide preliminary evaluative evidence of the different models. Among the insights highlighted by the authors were that:

- The peer-reviewed literature on cannabis legislation is very new and there are conflicting results depending on the data and methods used.

- Applying causality to data such as those on emergency department admissions is problematic given the range of other factors that could be influencing reporting or measurement.

- There is a lack of reliable and adequate data for a before-and-after comparison of the introduction of regulation.

The overall message was that the evidence base was still ‘insufficient to comment with any certainty on the impact of the changes that are occurring in the Americas’ (p. 6).1 Two years after publication, this continues to be the case.

Cannabis control in Europe

The EMCDDA’s webinar on cannabis control approaches in Europe brought together experts in the field to reflect on the current situation and possible future scenarios.2 There was consensus that the policy landscape and attitudes towards cannabis have changed in Europe, in line with the more health-focused policy context outlined above. Malta, Luxembourg, and Germany (see Box 1) are key examples of where this shift is happening. While the webinar identified a wide variety of issues, there were three that dominated the discussion:

- The restrictive nature of international drug laws and agreements

- The challenges of monitoring and evaluating the impact of policy change

- The risk of ‘corporate capture’.

Restrictions of international drug laws/agreements

While European countries may have internal drivers for changes to their cannabis laws, there are external influences that put limitations on the changes that can be made. The situation is complicated by the existence of international drug laws or agreements. Signatories must be cognisant of the restrictions they place on an individual country’s options vis-à-vis their drug laws. Two of those relevant in the European context are:

- The 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, to which all EU member states are signatories.6 Signatories commit to prohibit the production, manufacture, export and import of, and trade in scheduled drugs (which includes cannabis). It also limits their legal use to medical and scientific settings.

- The 2004 European Council Framework Decision (2004/757/JHA) allows for the possession and cultivation of cannabis for ‘personal consumption as defined by national law’ (Article 2.2).7 Anything beyond personal cultivation/consumption would be contrary to EU rules and regulations.

Therefore, any country that is a signatory of the UN convention and opens a regulated market is technically breaking international law, as is the situation with Uruguay, Canada, and certain US states. European countries would be breaking both agreements.

These restrictions have led to what was termed in the webinar as a ‘repetitious pattern’ in recent European policy. Some localities or whole countries propose sweeping changes to their cannabis laws, but as a result of international pressure modify their proposals to reflect more modest changes that sit within the 2004 EU Framework Decision (see Box 1).

Drug policy debates tend to be divisive and emotive. Tensions will inevitably arise within the EU if countries pursue models of regulation that violate these international agreements. Therefore, there is a need for constructive debate at European level to avoid tensions escalating among EU members over the changing policy landscape. It was argued that Europe is diverse and rules need to be made that respect that diversity.

At a more global level, it was noted that there is no appetite internationally to change the UN convention. However, as a group, countries that want to regulate cannabis could do so via a ‘late reservation’ to the convention. While this would be a challenging process, it presents an alternative to breaking international law. This was the approach successfully taken by Bolivia in relation to the cultivation and use of the coca leaf.

Monitoring the impact of policy change

Rigorous data and analysis are essential to be able to assess the impact of policy changes on the outcomes it sets to achieve. The webinar discussions illustrate that much work has yet to be done on developing this evidence base. For example, the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD), which collects comparable data on substance use among 15–16-year-old students to monitor trends within as well as between countries, was discussed. Among the key messages was that there is no simple correlation between a country’s cannabis-related penalties and its rates of lifetime or harmful use among young people. The relationship between a country regulating their cannabis market and the disappearance of the illicit market also needs further research. An overall message was that countries need to identify the outcomes they want to achieve by making changes to their cannabis laws and collect rigorous evidence to understand if these are being achieved and any unintended consequences of the changes.

Corporate capture

There was concern expressed by speakers about the corporate capture of regulated cannabis markets, as evidenced in the US and the increasing lobbying power of the industry globally. If not managed correctly, it was suggested that they would end up playing a similar role in the market and policy development as Big Tobacco and the alcohol industry. This would not be compatible with regulation models that have harm reduction at their core. In his closing remarks to the session, EMCDDA director Alexis Goosdeel argued that the needs of the user and the reduction of harms should be the drivers of policy decisions, not the interests of the cannabis industry.

Concluding comment

Changes in cannabis control are apparent in the Americas and more recently in Europe. These changes are not without their challenges. They have the potential to undermine the value of international laws and agreements more broadly. Where the motivation for changing policy is to reduce the harms caused by the status quo, the situation will need to be closely monitored and evaluated to ensure these outcomes are being achieved. Any unintended negative outcomes will also need to be monitored and minimised with the rollback or amendment of policies as necessary. A rigorous evidence base will be required to support these decisions. Reducing the harms will need to remain central to the policymaking and legislative process, and not be usurped by the business interests of the cannabis industry.

|

Recent developments in policy on non-medical (recreational) cannabis use in Europe Malta

Luxembourg Germany |

1 European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2020) Monitoring and evaluating changes in cannabis policies: insights from the Americas. Technical report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31594/

2 EMCDDA (2021) Cannabis control approaches across Europe [webinar]. 27 October 2021. Available online at: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/37090/

3 Council of the European Union (2020) EU drugs strategy 2021–2025. Brussels: Council of the European Union. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/33750/

4 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2016) Outcome document of the 2016 United Nations General Assembly Special Session on the world drug problem: our joint commitment to effectively addressing and countering the world drug problem. Vienna: UNODC. Available online at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/postungass2016/outcome/V1603301-E.pdf

5 For a clear description of the distinction between depenalisation, decriminalisation, regulation, and legalisation, visit: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/37091/

6 The 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, as amended by the 1972 Protocol. Available online at: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/33374/

7 Council of the European Union (2004) Council Framework Decision 2004/757/JHA of 25 October 2004. Brussels: Council of the European Union. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004F0757&from=EN

L Social psychology and related concepts > Legal availability or accessibility

MM-MO Crime and law > Substance use laws > Drug laws

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Policy > Policy on substance use > Drug decriminalisation or legalisation policy

VA Geographic area > Europe

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

VA Geographic area > Europe > Luxembourg

VA Geographic area > Europe > Germany

Repository Staff Only: item control page