Thiemt, Britta (2020) Hepatitis C screening and care for opioid substitution patients in Ireland. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 74, Summer 2020, pp. 24-26.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 74)

1MB |

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is now among the most common causes of cirrhosis and primary liver cancer in Europe.1 As HCV is a blood-borne virus, people who inject drugs are the primary risk group for contracting HCV, making up 80% of new infections.2 With opioid substitution increasingly being provided in primary care settings, they have an important role in HCV screening and treatment. In a 2018 study published in the Interactive Journal of Medical Research, Murtagh et al. investigated compliance in Irish primary care practices with guidelines on screening for HCV, other blood-borne viruses, and alcohol use disorder.3

About 74% of patients contracting HCV will become chronically infected, which is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.4 As symptom onset can be delayed by decades and result in considerable damage to the liver, screening for HCV is vital among opioid substitution patients, who are often at increased risk of HCV infection due to a history of drug injection. Additionally, opioid substitution patients often present with problem alcohol use, which can exacerbate the risk of liver disease. Hence, guidelines from the World Health Organization and Health Service Executive advise on addressing alcohol use with HCV patients.

Effective diagnostic technology (e.g. FibroScan) and treatment for HCV (direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment) are now available, but due to the high cost of treatment, guidelines prescribe prioritising patients with the highest clinical need.5 Additionally, scarce time and resources can complicate treatment within primary care. Given new options and plans to expand HCV interventions, the study’s aim was to investigate whether opioid substitution patients were receiving HCV screening and care in line with best practice guidelines.

Methods

The study used baseline data from the larger HepLink study on developing community-based HCV treatment interventions. Participants were opioid substitution patients recruited through non-probability sampling, which was deemed an acceptable method for the HepLink feasibility study. Of 63 general practices in the selected study area (Mater Misericordiae University Hospital catchment area in Dublin), 14 practices participated, each recruiting 10 participants. In total, 134 patients participated, 71.6% of whom were male. Their mean age was 43 years. Data were collected from patient records and included information on screening, treatment, and vaccination for blood-borne viruses (HCV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and HIV), and drug and alcohol use.6

Key findings

HCV

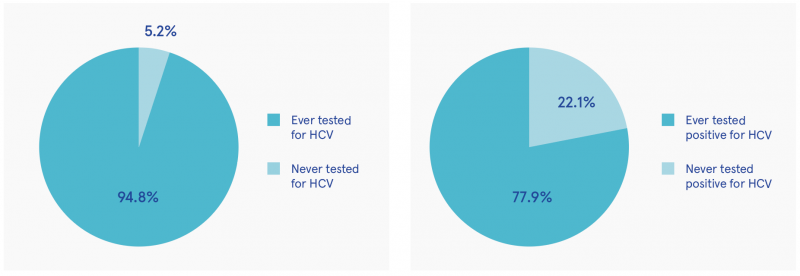

- HCV screening: In their lifetime, 94.8% of participants had been screened for HCV (23.9% in the past year); 77.9% of whom tested positive for HCV at least once (72% of patients tested in the past year; see Figure 1).

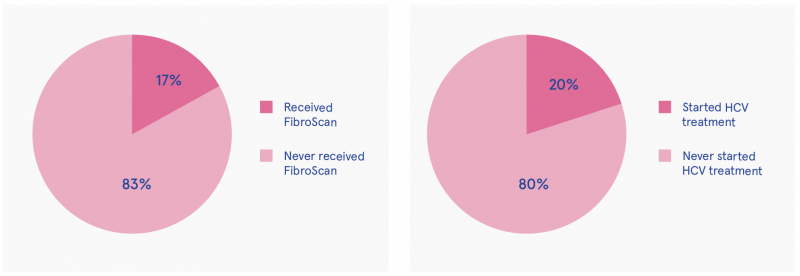

- Interventions: Only 17% of HCV-positive participants had had a FibroScan and only 20% had started HCV DAA treatment (3% in the past year; see Figure 2).

HIV and HBV

- HIV screening: 83.6% of participants had been screened for HIV in their lifetime (25.4% in the past year), 6.3% of whom tested positive (3% of patients tested in the past year).

- HBV screening: 66.4% of participants had been screened for HBV in their lifetime (22.4% in the past year), 8% of whom tested positive (3% of patients tested in the past year).

- Vaccination: 48.5% of patients had previously been vaccinated against HBV (8% in the past year).

Drug and alcohol use

- Alcohol screening: Clinical records showed that 30.6% of participating patients had been asked about their alcohol consumption by their general practitioners (GPs) in the past year.

- Interventions: Only 6% had received a brief intervention and 2.2% had a referral to specialist addiction services.

- Drug screening: 37.3% of participants’ last urine sample showed metabolites of non-prescribed drugs.

Discussion

Murtagh et al. welcome the high rate of HCV screening of 94.8% in this study, noting that this is a considerable increase from 69% in a 2003 study.7 In contrast, the low proportion of HCV-positive participants receiving treatment is concerning. The authors attribute this to the high cost of DAA treatment, necessitating the triaging of patients. They envisage that as antiviral medication becomes cheaper, its availability will increase for Irish HCV patients.

Less than one-third of patients had been screened for problem alcohol use, and brief interventions and referrals were only scarcely provided. While this represents an improvement from previous studies,8,9 the authors note that this is still insufficient given the risks to liver health of both HCV and alcohol use. Also considering the high proportion of opioid substitution patients with substance use in the study, Murtagh et al. conclude that GPs should be trained to provide more brief interventions and harm reduction education for their opioid substitution patients.

Figure 1: Percentage of participants ever screened for HCV (n=134) and results for those screened (n=127)

Figure 2: FibroScan assessment and intervention rate for HCV-positive participants (n=99)

Compared with previous findings in Ireland, the rates of patients in this study testing positive for HCV (77.9%) and for HBV (8%) are higher, whereas the rates for HIV (6.3%) are lower or similar.7,8 However, these differences should be interpreted with caution due to the variation in sample sizes and source of comparison data.

The study’s findings must be viewed in light of further limitations, including limited generalisability due to the non-randomised sampling technique and potential self-selection bias among participating GPs. Murtagh et al. also note the imperfections of clinical records as a data source on viral screening, as they do not capture care provided to patients in other practices. Nevertheless, the study provides important insights into the status quo of screening and care for informing the expansion of HCV treatment.

1 Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC and Roudot-Thoraval F (2013) The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol, 58(3): 593–608.

2 Lazarus JV, Sperle I, Matičič M and Wiessing L (2014) A systematic review of hepatitis C virus treatment uptake among people who inject drugs in the European region. BMC Infect Dis, 14, (Suppl 6): s16.

3 Murtagh R, Swan D, O’Connor E, et al. (2018) Hepatitis C prevalence and management among patients receiving opioid substitution treatment in general practice in Ireland: baseline data from a feasibility study. Interact J Med Res, 7(2): e10313.

4 Micallef JM, Kaldor JM and Dore GJ (2006) Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat, 13(1): 34–41.

5 Matičič M, Videčnik Zorman J, Gregorčič S, Schatz E and Lazarus JV (2014) Are there national strategies, plans and guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis C in people who inject drugs? A survey of 33 European countries. BMC Infect Dis, 14 (Suppl 6): s14.

6 Further measures not reported here included information on alternative HCV tests, hepatitis A virus (HAV), chronic illness, and healthcare use; see Murtagh et al. (2018) study.

7 Cullen W, Stanley J, Langton D, Kelly Y and Bury G (2007) Management of hepatitis C among drug users attending general practice in Ireland: baseline data from the Dublin area hepatitis C in general practice initiative. Eur J Gen Pract, 13(1): 5–12.

8 Klimas J, Anderson R, Bourke M, et al. (2013) Psychosocial interventions for alcohol use among problem drug users: protocol for a feasibility study in primary care. JMIR Res Protoc, 2(2): e26.

9 Klimas J, Henihan AM, McCombe G, et al. (2015) Psychosocial Interventions for Problem Alcohol Use in Primary Care Settings (PINTA): baseline feasibility data. J Dual Diagn, 11(2): 97–106.

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Communicable / infectious disease > Hepatitis C (HCV)

HJ Treatment or recovery method > Substance disorder treatment method > Substance replacement method (substitution)

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Health related issues > Health information and education > Communicable / infectious disease control

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Patient / client care management

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page