Guiney, Ciara (2020) Fostering understanding, empowering change: practice responses to adverse childhood experiences and intergenerational patterns of domestic violence. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 74, Summer 2020, pp. 17-19.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 74)

1MB |

In November 2019, Dr Sarah Morton and Dr Megan Curran of University College Dublin published the results of a Tusla-funded study, Fostering understanding, empowering change: practice responses to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and intergenerational patterns of domestic violence.1

The aim of this study was to examine the experiences of women at the Cuan Saor Women’s Refuge, a domestic violence service in Co Tipperary. The focus was to identify the level of ACEs experienced by the women who accessed the service. Based on the ACEs routine enquiry process, trauma-informed responses (TIRs) to women’s childhood experiences and the intergenerational transmission of trauma were examined as well as the role of ACEs routine enquiry and intervention in relation to infant mental health (IMH), a key area of work for childcare workers within domestic violence (p. 10).

Adverse childhood experiences

The term initially appeared in an American study that examined childhood experiences, such as neglect and abuse, along with challenges at home and health and wellbeing.2 Seven types of ACEs were identified in the initial study: psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; domestic violence; or living with household members who abused substances, were mentally ill or suicidal, or had been incarcerated.2 As research in this area has grown, the list has expanded to include, for example, parental separation (p. 11).1 Even so, how specific ACEs have been operationally defined has not been consistent across the various studies.

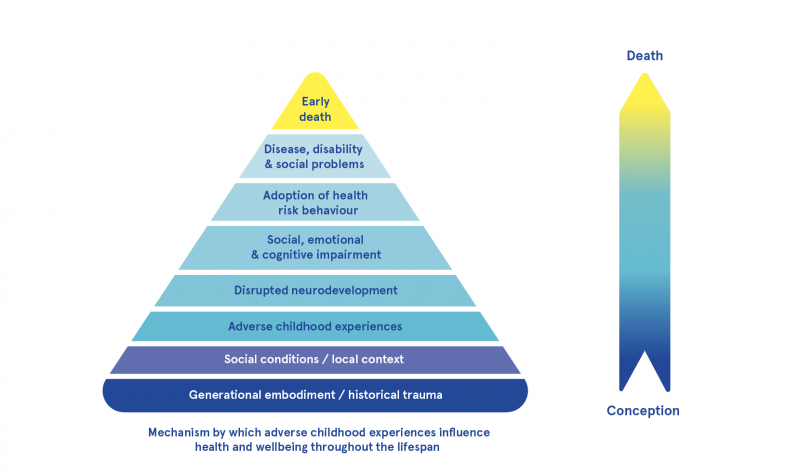

A strong relationship has been demonstrated between the seven ACEs and chronic illness and death. Moreover, those reporting four ACEs or more were likely to experience several health risk factors when they were older.2 Figure 1 identifies areas that can be influenced by ACEs.

Intergenerational effects are also associated with ACEs. This means that when children with an ACE become adults, they are inclined to engage in behaviour that develops possible ACEs for their children. In children, ACEs are viewed as a form of trauma that result in a chronic state of stress. When this stress occurs during critical phases of their development, it can result in physiological changes, impacting brain development, immunity, and hormones. In addition, it prevents them from forming secure attachment bonds, which in turn impacts on their ability to explore their social world and develop relationships.

Figure 1: The ACE pyramid

Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Methodology

The study carried out at Cuan Saor Women’s Refuge was an action-research approach and involved a mixed-methods design using quantitative and qualitative data. It was carried out over nine months and broken down into three phases:

1 ACEs routine enquiry: Women who accessed the refuge over a three-month period anonymously completed a 10-question ACEs questionnaire (n=60).

2 Qualitative data: These were collected via practitioner inquiry groups consisting of Cuan Saor staff (n=10). Three inquiry groups which lasted 90 minutes approximately were run every 4–6 weeks.

3 Interagency cooperative inquiry group (n=7): This examined the possibility of integrating ACEs into wider interagency work, particularly in the areas of IMH. This consisted of two inquiry groups that lasted 90 minutes approximately. They were run four weeks apart.

Results

Quantitative

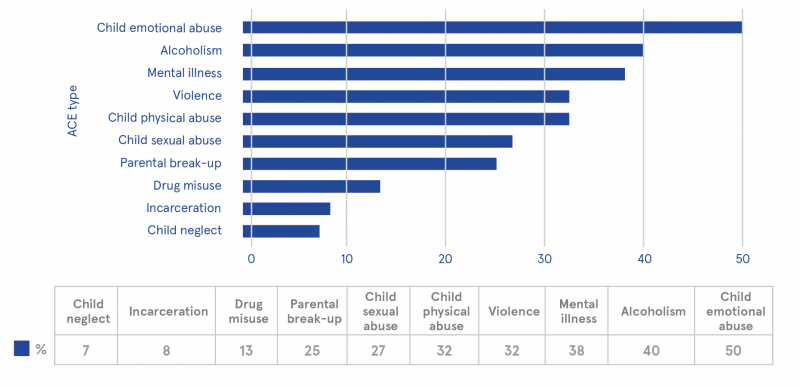

- The mean ACEs score for service users was 2.7.

- 18% of service users reported having no ACEs in childhood.

- 58% experienced at least two ACEs.

- 33% experienced four or more ACE events in childhood.

- 40% experienced alcoholism in childhood.

- 13% experienced drug misuse.

Figure 2 identifies the most common types of ACEs by percentage experienced by Cuan Saor service users from highest to lowest.

Figure 2: Most common types of ACEs experienced by Cuan Saor service users (n=60)

Qualitative

Several qualitative themes emerged:

- Implementing ACEs routine enquiry:

- Training

- Implementation

- Lessons from ACEs routine enquiry:

- Relevance of the ACEs tool

- Responding to disclosures of trauma

- Timing ACEs routine enquiry within the helping process

- Understanding and empowerment of users

- Interagency work.

Implications

Several implications were put forward by the authors. These were based on the results of this study and the wider ACE literature. Four areas were identified: service users, practitioners, organisations, and funders.

Service users

Practitioners found that the completion of the ACEs routine enquiry by services users resulted in the identification of practice issues and responses. This information was deemed helpful to others implementing the ACEs routine enquiry. Practitioners also found that using the ACEs routine enquiry helped service users to come to terms with past experiences, leaving them in a better position to address the impact of the ACEs on themselves and their children. However, the appropriateness of the ACEs routine enquiry for older women was questioned.

Practitioners

ACE is one of several TIRs that has been reviewed and put into practice across services. However, practitioners raised some concerns:

- Time and resources for appropriate training and support around the implementation of ACEs to deal with disclosures that may change the service user emotionally

- The importance of boundaries and limitations when dealing with these issues

- The impact of dealing with ACEs on the practitioner.

Organisations

Organisations need to independently consider the best way to implement a TIR, the instrument to be used, training and support for practitioners, follow-up and referral services, and the evaluation process. From an interagency perspective, it would be important to determine whether non-governmental agencies and community organisations would be in a better position to pilot this approach in light not having the same constraints as larger organisations, for example, Tusla.

Funders

How to develop and fund TIRs particularly ACEs in health and social care was deemed to be challenging. To implement change, several factors need to be considered: the evidence; development and implementation of the intervention; practitioner training; getting the organisation on board; and resources. This study used a limited budget, existing supervision, and support structures within Cuan Saor and strong interagency relationships between IMH practitioners. This infrastructure may not always be available, which can further impact on funding.

Limitations and further research

As acknowledged by the authors, the questionnaire used in this study provided insight into the level and types of ACEs experienced by domestic violence users, thus enabling the implementation of a more responsive service. However, this approach was not intended to determine whether a causal link existed between ACEs in childhood and later outcomes. In addition, only practitioners took part in the enquiry groups. Also, in terms of future research, the views and impact of ACEs on female service users should also be assessed.

1 Morton S and Curran M (2019) Fostering understanding, empowering change: practice responses to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and intergenerational patterns of domestic violence. Tipperary: Cuan Saor Women’s Refuge. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31507/

2 Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of deaths in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med, 14(4): 245–258. Available online at: https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(98)00017-8/pdf

F Concepts in psychology > Psychological stress / emotional trauma / adversity > Adverse childhood experiences (ACE)

L Social psychology and related concepts > Family > Family and kinship > Family support

MM-MO Crime and law > Crime and violence > Crime against persons (assault / abuse)

MM-MO Crime and law > Crime and violence > Crime against persons (assault / abuse) > Intimate partner abuse (domestic violence)

T Demographic characteristics > Child / children

T Demographic characteristics > Affected family members / concerned persons

T Demographic characteristics > Child of person who uses substances

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page