Lyons, Suzi (2020) Risk of drug-related poisoning deaths and all-cause mortality among people who use methadone. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 73, Spring 2020, pp. 22-24.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 73)

758kB |

Methadone is the most commonly prescribed opioid substitution treatment in Ireland. A retrospective cohort study was carried out in all specialist addiction services in Dublin South West and Kildare looking at the risk of death associated with interruptions in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) for the years 2010–2015.1

Methods

Using data from the Central Treatment List and the Health Service Executive Methadone Treatment Scheme, start and end dates for patient MMT were identified from methadone dispensing data. This information was then linked to mortality data from the National Drug-Related Deaths Index (NDRDI) and prescription data from the General Medical Services. The researchers were therefore able to categorise the treatment status for every day for each patient (addiction services, primary care, prison, out of treatment). ‘In treatment’ was defined as a continuous daily supply of methadone. If a patient did not receive a new prescription within 7 days after the end of the last prescription, they were considered to be ‘off treatment’. The patient remained off treatment until they received a new prescription.

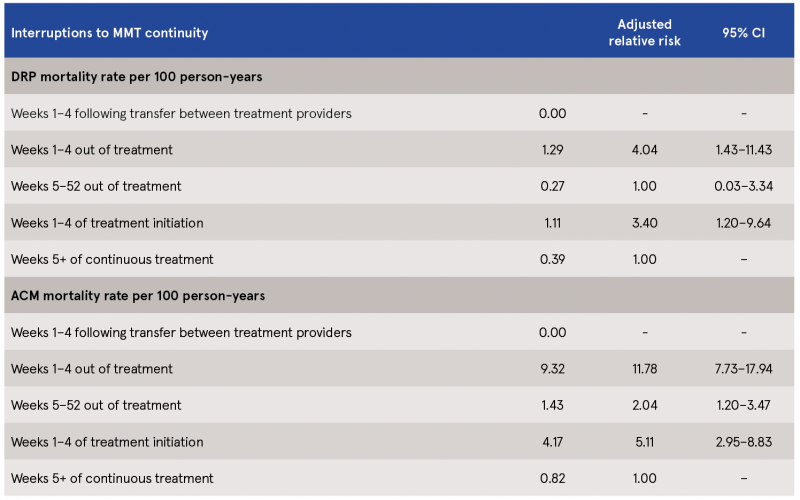

There were five groups within the study: weeks 1–4 following transfer between treatment providers; weeks 1–4 out of treatment; weeks 5–52 out of treatment; weeks 1–4 of treatment initiation; and weeks 5+ of continuous treatment. A drug-related poisoning (DRP) death was classified as the primary outcome measure, while an all-cause mortality (ACM) death was classified as the secondary outcome.

Findings

The study included 2,899 patients over the six-year study period, equating to 13,300 person-years. The median follow-up period was 5.5 years. The majority were male (63.3%), with a median age of 33.9 years. Forty-nine per cent (48.5%) of patients were found to have transferred, on average, three times between services. Most of the transfers were back and forth between prison and addiction services. Many patients included in the study had evidence of physical ill-health and/or mental health problems, with 66.9% reporting two additional problems, most commonly mental health problems (66%), diseases of the digestive system (34%), and diseases of the respiratory system (24%). The study also recorded the median methadone dose at the last treatment episode, as follows:

> 40.5% median dose <60 mg

> 56.1% median dose 60–120 mg

> 3.4% median dose ≥120 mg.

Of the 2,899 patients included, 154 (5.3%) were known to have died. There were no deaths recorded in weeks 1–4 following transfer between treatment providers. Of those who died, one-third (n=55, 36.2%) were a DRP (crude DRP mortality rate of 0.41 per 100 person-years [95% CI: 0.30–0.52]). After adjusting the analysis for other factors, the risk of DRP was highest in weeks 1–4 out of treatment and weeks 1–4 of treatment initiation (see Table 1). The risk was higher for women and increasing age. The crude ACM was higher than DRP, with a rate of 1.14 per 100 person-years [95% CI: 0.96–1.32]. As with DRP, the risk of ACM was highest in weeks 1–4 out of treatment and weeks 1–4 of treatment initiation (see Table 1). The risk of ACM was higher for those with a recorded disease of the circulatory system and increasing age, while the risk was reduced for those with a history of imprisonment.

The authors noted that the 7-day rule used to categorise treatment status could be a bias in the study, as some patients may not have stopped treatment. Therefore, they conducted the analysis using 14 days instead of 7 days. This did not change the results, with the exception that the risk of ACM for weeks 1–4 in treatment did not remain significant in the multivariate analysis.

The strength of the study is that it included a large number of patients, representing almost one-half of all those in MMT treatment during that time. There was a long follow-up time and the study utilised a number of existing databases to account for interruptions to treatment and mortality.

Table 1: DRP and ACM mortality rates per person-years and adjusted relative risk by interruptions to MMT continuity

Limitations

A number of weaknesses and biases were acknowledged. There were other factors and confounders associated with interruption of treatment that could not be accounted or controlled for. One example cited was where a patient may have left treatment, moved into recovery and had stopped problem opioid use, and had therefore reduced their risk of mortality compared with those who relapsed and returned to treatment. The researchers used a 12-month limit for follow-up after stopping treatment to control for this potential confounder. The study did not include transfers to/from hospital, as hospitals are not required to report to the Central Treatment List. Therefore, given the high proportion of patients who also suffered from physical illnesses, it may be that those off treatment had been admitted to hospital for treatment for those illnesses, which might have influenced the results. Patients on Suboxone were also not included in the study.

Conclusions

This study confirms that the first 4 weeks after treatment initiation and after stopping treatment have the highest risk for mortality among patients in MMT in Ireland. While this trend is similar to findings from United Kingdom studies, mortality rates observed in this study were higher. This may be due to ageing among problem opioid users along with higher levels of comorbidity. The increased risk at initiation could be attributed to continued use of illicit opioids or other respiratory depressant drugs, or could be tolerance related. There were no deaths recorded in the first 4 weeks after transfer between services. Given that many of those transfers were to and from prison, this may reflect the policy of keeping a person’s place in community MMT until they are released from prison.

The authors recommend further investigation into the risks for patients caused by transfer between services. Seeing that the study shows the greatest risk of mortality at treatment initiation or after treatment stops, the authors also recommend closer monitoring of opioid tolerance at these times as well as relapse prevention strategies, which would include provision of take-home naloxone.

Durand L, O’Driscoll D, Boland F, Keenan E, Ryan B, Barry J, et al. (2020) Do interruptions in the continuity of methadone maintenance treatment in special addiction settings increase the risk of drug-related poisoning deaths? A retrospective-cohort study. Addiction, Early online. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31615/

B Substances > Opioids (opiates) > Opioid product > Methadone

G Health and disease > Respiratory / lung disease

HJ Treatment or recovery method > Substance disorder treatment method > Substance replacement method (substitution) > Opioid agonist treatment (methadone maintenance / buprenorphine)

P Demography, epidemiology, and history > Population dynamics > Substance related mortality / death

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page