Murphy, Laura (2017) Drug-related intimidation. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 62, Summer 2017, pp. 25-27.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet issue 62)

700kB |

Drug-related intimidation (DRI) negatively impacts the health and wellbeing of individuals, families, communities and the functioning of local agencies who serve them. Intimidation can be explicit or implicit, involving actual, threatened or perceived threats of violence or property damage. It can leave targeted individuals feeling helpless, isolated, demoralised and fearful. The Health Research Board (HRB) recently published an evidence review, conducted on behalf of the Department of Health’s Drugs Policy Unit, to identify international best practice, community-based responses to DRI1. The review focused on intimidation carried out by those involved in the distribution of drugs, including disciplinary intimidation, used to enforce social norms within the drug distribution hierarchy, to discourage or punish informants, or as a means to reclaim drug debt, and successional intimidation, used to recruit new members or gain control over networks or territory.

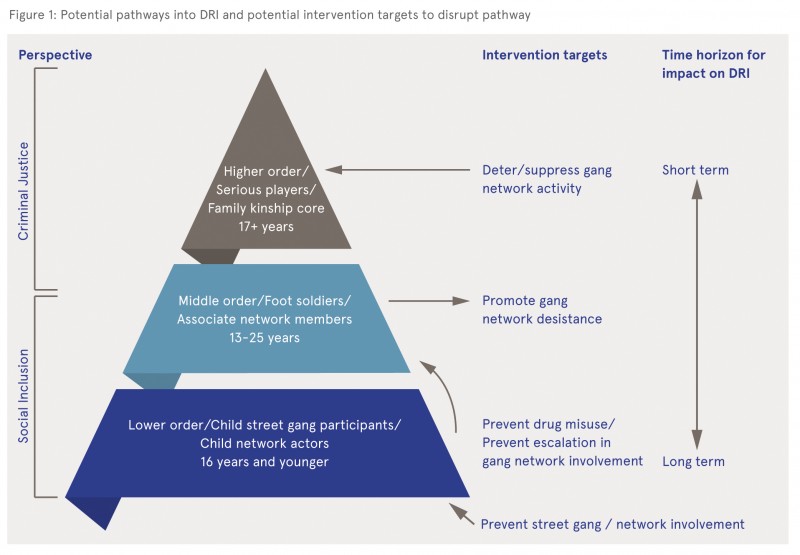

The international literature evaluating direct responses to DRI was scant. Therefore, the review drew on three Irish studies describing the underlying structure and operation of Irish criminal and drug distribution networks to develop a conceptual framework for understanding potential pathways into DRI and potential intervention targets to disrupt this pathway (Figure 1). Despite using different methodologies in different Irish communities, these studies consistently described a three-tiered, hierarchical network structure involving: (1) a lower tier of highly disadvantaged young people generally involved in bullying, assaulting, stealing, vandalising, and spreading fear on behalf of the network; (2) a middle tier of young people typically engaged in high-risk, low-reward activities, such as transporting, holding or dealing drugs, carrying guns, and conducting shootings, beatings and serious intimidation; and (3) a higher tier of serious players, often formed around a kinship core. This framework suggests a number of potential intervention targets that differ in (a) their approach, whether based on a criminal justice or social inclusion perspective; (b) their target, whether they aim to prevent gang joining, prevent escalation in gang involvement, intervene to promote gang exit, or deter or suppress gang activity; and (c) the time horizon of their impact, whether short or long term.

Guided by this framework, the review sought to answer the following questions:

What community-based interventions are effective in:

- Preventing entry into gang networks among at-risk children?

- Promoting gang exit among gang-involved young people?

- Deterring or suppressing drug gang-related crime, intimidation and/or violence?

The review drew on gang control literature, which evaluates approaches to target the group processes and structures involved in perpetuating a cycle of community intimidation and violence. The premise of the review was that reducing gang activity by targeting the underlying structure and functioning of drug/gang networks directly would indirectly reduce the fear, intimidation and violence that they create in communities.

Methods

The review team (a) systematically searched 10 bibliographic databases, the publication sections of key international organisation websites, and the reference lists of included studies; (b) screened 1251 records on title and abstract and 136 on full text; and (c) included 45 reviews or studies in the final synthesis. The included literature was drawn from 12 countries, predominately the United States.

Findings

Gang prevention

Universal: Most universal prevention programmes identified were school based, with or without parental involvement. Collectively, effective programmes had positive effects on short-term outcomes, such as problem solving, empathy, conduct problems, antisocial behaviour, delinquency, aggression, and long-term outcomes such as substance initiation and use, violence and crime. Key features of effective programmes were those with positive goals, parental involvement, group-based and interactive techniques, trained professional facilitators, manualised content, and frequent content delivery. One gang-specific prevention programme (Gang Resistance Education and Training ‒ GREAT II) showed promise in preventing gang membership; however, the evidence was drawn from only one large-scale study.

Selective: Selective prevention programmes target those at higher than average risk and aim to prevent antisocial behaviour, substance use, delinquency and gang membership. A number of selective prevention programme models were identified. Good evidence suggests that skills-based programmes targeting parents of at-risk children aged 0‒3 years produce immediate short-term impacts on child behaviour and parenting practices and improvements in long-term delinquency outcomes. Youth mentoring had small beneficial effects on conduct and recidivism. There was no evidence available on the effect of education and employment opportunities provision for preventing gang involvement. Community sports programmes had weak evidence that they may reduce youth crime. There was strong evidence that deterrence or discipline-based programmes, such as Scared Straight or boot camps, are ineffective and potentially harmful. Selective prevention programmes shared the same key features as effective universal prevention programmes.

Indicated: Indicated prevention programmes target individuals already engaged in high-risk behaviours, such as opposition behaviour, conduct disorder, antisocial behaviour, substance use and/or delinquency to prevent gang membership, gang embeddedness, and criminal activity. These include (a) therapeutic approaches: functional family therapy, multisystemic therapy, or multidimensional family therapy; and (b) gang-specific wraparound approaches, which are individualised programmes of care identifying the precise supports needed by an individual and their family and providing them for as long as needed. There is good evidence that indicated prevention programmes, incorporating therapeutic principles that aim to create positive changes in the lives of young people and their families, prevent negative outcomes. Risk assessment, using tools such as the Gang Risk of Entry Factors tool, ensures appropriate targeting of these programmes.

Intervention (gang exit)

Gang alternatives interventions: Gang alternatives interventions seek to motivate gang-involved youth to leave their gang, support them in doing so, and create opportunities for meaningful occupation outside of the gang. Five identified gang alternatives interventions, involving street outreach or opportunities provision programmes, had limited evidence of no or negligible impact on gang membership status, gang-related crime or violence.

In-depth analysis of desistance process: To address this gap in the available evidence, an in-depth analysis of primary peer-reviewed studies providing descriptive data – either qualitative or quantitative – on the nature or process of gang desistance was conducted. Analysis of this data suggested that gang members performed desistance work – they made an effort to reform their identity, pursue prosocial values, and seek belonging among prosocial groups. Gang exit requires this desistance work, which enables former gang members to become the primary agents in their exit from the gang.

Suppression

Gang activity prevention: Gang activity prevention focuses on preventing the actions of gangs responsible for the most harm in the community by targeting specific activities, places or behaviours. Evidence for these approaches was limited in quantity and quality. Promising interventions in this category were carefully crafted civil gang injunctions, environmental design interventions, and urban renewal efforts. The latter had positive impacts on crime, while improving police legitimacy and communities’ sense of control and cohesion.

Gang activity suppression: Gang activity suppression interventions seek to suppress or deter the harmful activities of gangs. ‘Pulling levers’-focused deterrence strategies had the largest direct impact on crime and violence of all suppression strategies reviewed. Key features of successful focused deterrence approaches include: targeting specific crimes rather than specific gangs; strong, swift and consistent enforcement actions, alongside meaningful offers of support by community agencies; establishing a multiagency task force to lead and coordinate the initiative; and engaging community members.

Comprehensive approaches: Comprehensive gang control programmes, combining prevention, intervention and suppression, have shown promise but achieved mixed effects. Mixed effects have been attributed to poor model specification, poor implementation fidelity and an overly complex model given local capacity to coordinate and implement it. It is generally accepted that comprehensive approaches, designed within local capacity and resources, are likely to be the most appropriate approach to tackling gang-related crime, intimidation and violence in communities with acute gang problems.

Key messages

- Comprehensive approaches should be developed using the best available information on what works within each of the three domains – prevention, intervention and suppression. The reviewed literature suggests:

-

- Early intervention programmes involving schools and families, supporting positive goals, involving skills training, delivered by trained professionals and incorporating therapeutic approaches for those at higher risk according to risk assessment.

- An assets-based approach to supporting the desistance work (efforts to reform identity and find belonging in prosocial groups) of gang members exiting their gang.

- A ‘pulling levers’-focused deterrence strategy designed with community involvement.

- Comprehensive approaches should be designed to be feasibly delivered at a consistent high quality and sustained over time within local financial resources and organisational capacity.

- Any comprehensive approach requires stakeholder partnership among social services, schools, law enforcement, probation and parole, the courts system, and community representatives. Good coordination and communication is required to maintain this partnership.

- Engaging the local community and community leaders is important to the legitimacy of the effort. Community has a role to play in defining key issues, identifying young people who require support, designing responses, intervention delivery and increasing the legitimacy of the effort.

- Given the current state of the evidence, any approach that is implemented should:

-

- Have a theoretical underpinning

- Be informed by local data

- Be clearly articulated in advance

- Be implemented according to a protocol with deviations documented

- Include a process and outcome evaluation

- Lastly, researcher‒practitioner partnerships may enable data-driven approaches, robust evaluation, and good implementation fidelity.

Murphy L, Farragher L, Keane M, Galvin B and Long J (2017). Drug-related intimidation. The Irish situation and international responses: an evidence review. Dublin: Health Research Board, 2017. Available at https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/27333/

A Substance use and dependence > Substance related societal (social) problems

L Social psychology and related concepts > Interpersonal interaction and group dynamics > Social support

MM-MO Crime and law > Organised crime

MM-MO Crime and law > Crime > Substance related crime > Crime associated with substance production and distribution

MM-MO Crime and law > Crime and violence > Crime against persons (assault / abuse)

MM-MO Crime and law > Crime and violence > Crime against persons (assault / abuse) > Intimidation

MM-MO Crime and law > Justice system > Community anti-crime or assistance programme

MM-MO Crime and law > Justice system > Community anti-crime or assistance programme > Community policing / police

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page