Guiney, Ciara and Dillon, Lucy (2024) Drug use and current alternatives to coercive sanctions in Ireland. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 89, Autumn 2024, pp. 4-10.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet 89)

1MB |

In July 2024, the Centre for Justice and Innovation published a report, presented by Tony Duffin, the chair of the National Drugs Strategy Strategic Implementation Group 5 (SIG-5), which aimed to map existing alternatives to coercive sanctions (ACS) for individuals found in possession of controlled drugs for personal use in Ireland.1 The authors explored how ACS are delivered in Ireland, stakeholders’ views on how these could be improved, and the potential for the expansion of ACS in the Irish context.

Strategic Implementation Group 5

The mid-term review of the National Drugs Strategy resulted in the identification of six strategic priorities that needed to be actioned and implemented.2 Responsibility for these priorities was given to six strategic implementation groups (SIGs), who are required to report their actions to the National Oversight Group on a quarterly basis. SIG-5 is responsible for actions related to the promotion of alternatives to coercive sanctions for drug-related offences. The 2024 report addresses Action 5.4 to ‘Strengthen policy and practice with regard to alternatives to coercive sanctions and share learning with EU member states’ (p. 1).1

Literature review

The authors carried out a ‘light touch literature review’, which gleaned knowledge from systematic reviews and meta-analyses within the European context. Within the Irish context, statistical trends were explored using Government data. Several themes were presented.

Alternatives to coercive sanctions

ACS have been defined by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) as ‘measures that are rehabilitative, such as treatment, education, aftercare, rehabilitation and social reintegration’ (p. 6).3 While they cover a wide range of interventions, they also vary in terms of the types of offences they deal with and the stage of the judicial process in which they are accessed (e.g. pre-arrest or post-sentencing). In Ireland, much of the public debate on ACS is focused on responding to possession of drugs for personal use. For example, such as in the Health Diversion Programme and in the Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use recommendation that ‘the State should introduce a comprehensive health-led response to possession of drugs for personal use’ (p. 13). However, the ACS identified in this report have a broader scope and deal with ‘minor drug offences in Ireland’ (p. 1).1 They also represent interventions that deal with people at various stages of the criminal justice system.

Rationale for using ACS

The authors put forward several reasons to explain why the criminalisation of drug possession and low-level drug offences continue to be problematic in Europe, such as increased pressure on justice systems and prisons, the failure of sanctions to prevent drug use, and the subsequent social harms produced by them.

In Ireland, drug possession for personal use is an offence under Section 3 of the Misuse of Drugs Act, 1977 and accounts for around 70% of all controlled drug crime. While this offence can result in a fine and or up to 7 years’ imprisonment, in practice cases that appear before the Courts are more often dismissed or result in fines, probation, community service, or suspended sentences (p. 6). In light of this, further pressure is placed on criminal justice resources, in particular probation. The authors have acknowledged that illicit drug use continues to rise in Ireland, which is consistent with findings across Europe.

Benefits of ACS

The link between drug use and dependence and criminality has been well-documented.5 In contrast to the use of sanctions, incarceration, and decriminalisation, it has been shown –despite limitations in how ACS studies have been conducted – that treatment, education, aftercare, rehabilitation, and social reintegration are related to less drug use and related harms.6 This is achieved by using a multifaceted approach:

- Individual level: Targeting addiction and stigma.

- Social level: Easing public health problems along with the level of acquisitive crimes.

- State level: Reducing the pressure on resources (prisons and courts) within the criminal justice system.

The evidence also suggests that there is a negative association between ACS and reoffending.6

Types of ACS

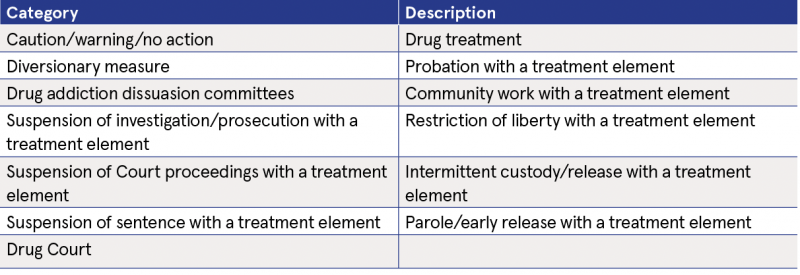

In 2016, the European Commission identified 13 distinct ACS initiatives (see Table 1).7

Table 1: Types of alternatives to coercive sanctions

Source: Adapted from European Commission (2016, p. 16)7

Barriers to implementation

Based on the findings of their literature review, the authors identified several common barriers to implementation:

- Professionals implementing ACS do so at their own discretion, which is influenced by their understanding of the nature of drug use, whether a health-driven issue, a criminal one, or their attitudes towards people who take drugs.

- There is limited feedback regarding the effectiveness of ACS.

- There is a lack of awareness by prosecutors and judges regarding the ACS available. This issue was identified in the Drug Treatment Court in Ireland and by the European Commission.7

- Funding and legislation can limit the mandate and role of ACS.

Methods

This research involved a mixed method approach. Professionals were invited by the Department of Health to complete a survey.

The survey questions centred on the details of local initiatives and their background; agencies involved (leading/delivering/funding); how they operated; eligibility criteria; and whether programmes were evaluated.

Thirteen responses were received, of which only five were complete. Interviews were carried out with practitioners/managers working in relevant agencies across Ireland, such as the Health Service Executive (HSE) (Cork Court Referral Programme), An Garda Síochána, Dublin Drug Treatment Court, and Letterkenny CDP Start Project.

Results

The results indicated that:

- Most of the initiatives were localised, except for the Adult Caution Scheme.

- Operation timeframes varied across projects.

- The longest-running initiative was the Dublin Drug Treatment Court.

- Initiative funding came mainly from the Department of Health, Department of Justice, Local Drug and Alcohol Task Forces, and the Probation Service. However, agencies sometimes lent resources or money from fines diverted into programmes.

- The response rate was low, and the limited interviewee awareness regarding ACS projects suggests that knowledge of current ACS practice is limited across the sector.

Caution/warning/no action

Adult Caution Scheme

The Adult Caution Scheme was established in 2005 as an alternative to crimes where prosecution was not in the public interest. In December 2020, possession of cannabis or cannabis resin was added to the scheme. It can only be used once and at the discretion of An Garda Síochána, who factor in a range of circumstances such as behaviour, guilt, victim’s views, and public interest. The type, quantity, and volume of cannabis or cannabis resin are also factored into the decision.

Between December 2020 and February 2024, the number of cautions issued for the personal possession of cannabis was 5,139.8 However, in the same period, 17,124 people were issued with a charge/summons for simple possession of cannabis or cannabis resin,7 which suggests that the scheme is not being used consistently.1

Diversionary measures

Law Engagement and Assisted Recovery (LEAR) Programme

The LEAR initiative, which has been based in Dublin City since 2014 and Limerick City since 2023, targets individuals who:

- Have committed multiple offences

- Are aged 18 years and over

- Are experiencing complex and multiple needs in relation to addiction, public injecting, homelessness, rough sleeping, antisocial behaviour, begging, criminality, and mental health.

Referrals are made directly by Gardaí to a local case worker. Ongoing support includes needs assessment and signposting to appropriate services with the aim of addressing offending behaviour and reducing harm. Progress is monitored every 6 months by both the referring Garda and the case worker. Participation in the programme is voluntary.

An evaluation of the programme pilot showed that:

- 40% of clients had access to more stable accommodation.

- 26% were able to access treatment for drugs and alcohol.

- Antisocial behaviour had reduced (37%).

- The majority of participating individuals remained engaged with the programme (90%).

Drug Courts

The Drug Treatment Court (DTC) was initially established in 2001 in Dublin to deal with offenders committing offences as a result of illicit drug use. The aim is to reduce crime via treatment and rehabilitation. Two other Drug Courts have since developed: one in Louth, which also covers Meath, in 2018 and the other in Cork City in 2019. These were developed under a local accord and hence are not officially sanctioned; as a consequence, they do not have access to the same resources as the Dublin DTC. Since 2022, there have been 33 referrals to the Louth DTC, of which 13 graduated. In 2023, some 25 individuals were admitted to the programme. Up to September 2023, some 189 young cocaine users had been referred to Cork DTC. Limited data are available on programme outcomes; however, attendance for intervention screening has been high (93%), of which 11% received referrals to drug and alcohol services.

Drug treatment

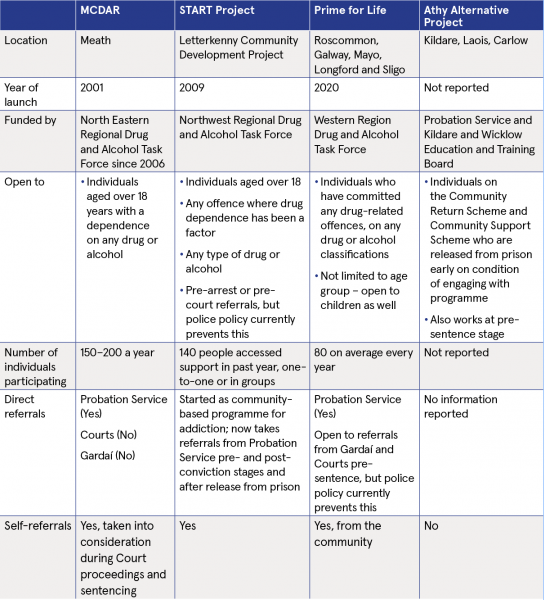

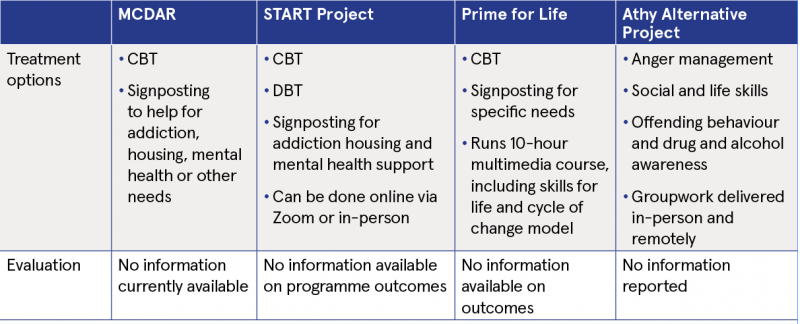

The authors report on four drug treatment programmes: Meath Community Drug and Alcohol Response (MCDAR); Prime for Life (Roscommon, Galway, Mayo, Longford and Sligo); the START Project (Donegal); and the Athy Alternative Project (Kildare, Laois and Carlow).

Table 2 provides a description of the main features of the drug treatment projects.

Table 2: Summary outline of drug treatment projects

Source: Extracted from Centre for Justice Innovation (2024, pp. 13–14)1

CBT: Cognitive behavioural therapy; DBT: Dialectical behaviour therapy.

Please note that the Prime for life (PFL) programme utilises Motivational Interviewing and not CBT. See the revised Drug use and current alternatives to coercive sanctions in Ireland for details

Reflections

Through their interviews with stakeholders, the authors identified five overarching themes.

1 There are opportunities and enthusiasm to develop pre-arrest and point-of-arrest diversion offers: They found a ‘solid foundation’ (p. 15) of Court and post-Court diversion into treatment programmes, but the options that focused on pre-arrest and point-of-arrest diversion for drug-related offences among adults were much more limited. ACS were found to have broad support among the Probation Service, court workers, some of the judiciary, the drug and alcohol treatment providers and their networks. However, attitudes among An Garda Síochána towards ACS were more varied.

2 Funding is available from various sources but can lack consistency: While existing ACS were managed with funding from a variety of sources, it was suggested that increased, specific management of HSE funding for each ACS activity may help to provide better national awareness of what is being delivered and the impact it is having.

3 There are gaps around learning and evaluation: Given that existing ACS are being funded and managed at the local level and are often driven by a small number of stakeholders, there has been little opportunity for learning from and evaluation of the various interventions and the impact they are having.

5 There is a lack of awareness around some existing projects: Projects tended to be local and not all stakeholders working in the area were aware of the ACS as an option in their locality.

5 There is a promising environment for change: Given the broad support of ACS from stakeholders and the recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use, the authors argue that this has created an environment amenable to the expansion of ACS and particularly the availability of pre-arrest and point-of-arrest diversion.

Conclusion

In the report foreword, Tony Duffin, chair of SIG-5, stated that ‘looking ahead it is important that we deliver streamlined processes to ensure alternatives to coercive sanctions are accessible, cost-effective, and efficient, offering individuals every chance to thrive and avoid the negative impact of criminal penalties’ (p. 1).1

Moreover, in the executive summary, he concluded that:

The findings of this report lead us to believe that at present Ireland is at the precipice of transforming how its justice system responds to drug use in a more effective and humane way. It has shown how local initiatives have identified a need for ACS and have begun to implement them throughout the country in the absence of a national ACS for possession of drugs for personal use. The innovative work undertaken across the system to support individuals with their drug use is laudable, but it is missing opportunities earlier to prevent offending and re-offending and improve health outcomes for its citizens. (p. 3)1

1 Centre for Justice Innovation (2024) Drug use and current alternatives to coercive sanctions in Ireland: Mapping the existing alternatives to coercive sanctions for people found in possession of controlled drugs for personal use. Dublin: National Drugs Strategy Strategic Implementation Group 5 (SIG-5). Available from:

https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/41354/

2 Drugs Policy and Social Inclusion Unit (2021) Mid-term review of the national drugs strategy, Reducing Harm, Supporting Recovery and strategic priorities 2021–2025. Dublin: Department of Health. Available from: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/35183/

3 European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2015) Alternatives to punishment for drug-using offenders. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available from: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/24320/

4 The Citizens’ Assembly (2024) Report of the Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use, Volume 1. Dublin: The Citizens’ Assembly. Available from: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/40393/

5 Rooney L (2021) Informing & supporting change: drug and alcohol misuse among people on probation supervision in Ireland. Dublin: The Probation Service. Available from: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/35133/

6 Tomaz V, Moreira D and Cruz OS (2023) Criminal reactions to drug-using offenders: a systematic review of the effect of treatment and/or punishment on reduction of drug use and/or criminal recidivism. Front Psychiatry, 14: 1–19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.935755

7 Kruithof K, Davies M, Disley E, Strang L and Ito K (2016) Study on alternatives to coercive sanctions as response to drug law offences and drug-related crimes: final report. Brussels: European Commission. Available from: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6e9f22b4-aa5a-11e6-aab7-01aa75ed71a1

8 McEntee H (2024) Parliamentary Debates Dáil Éireann. 22 Feb 2024. Vol. 1050, No. 2: Question 37 – Substance Misuse. Available from: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/40543

MM-MO Crime and law > Criminal penalty / sentence

MM-MO Crime and law > Criminal penalty / sentence > Community service > Probation or parole

MM-MO Crime and law > Justice and enforcement system

MM-MO Crime and law > Justice system > Court system > Drug court

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page