Dillon, Lucy (2022) Global Drug Policy Index. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 80, Winter 2022, pp. 6-8.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 80)

1MB |

On 8 November 2021, the Global Drug Policy Index (GDPI) was launched.1 The GDPI is a composite index that scores and ranks countries on how their national drug policies and their implementation align with a set of indicators that reflect the United Nations (UN) recommendations on human rights, health, and development. These are laid down in the UN System Common Position on drugs and, more specifically, the related 2019 UN report, What we have learned over the last ten years: a summary of knowledge acquired and produced by the UN system on drug-related matters.2,3

Background

The GDPI is the output of the project ‘The Global Drug Policy Index (GDPI): A bold new approach to improve policies, harm reduction funding, and the lives of people who use drugs’, which was supported by the Robert Carr Fund and led by the Harm Reduction Consortium.4 It has been developed by civil society and community organisations in partnership with academia. It is grounded in its developers’ belief that global drug policies that are based on a ‘war on drugs’ narrative exacerbate harms and lead to widespread human rights violations. The Index is a tool to promote policy reforms in favour of more humane responses and sets out to provide a reliable accountability and evaluation mechanism in the field of drug policy.

Methodology

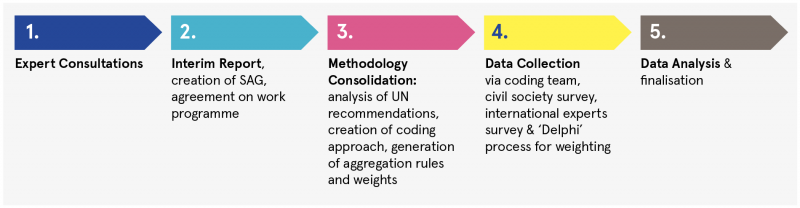

The GDPI was developed through a complex five-step methodological process (see Figure 1). The process involved consultations, identification of indicators, thematic policy clusters and dimensions, data collection, and analysis. Data were collected through desk-based research, a civil society survey, a survey of drug policy analysts, and other structured consultation with other stakeholders. Weighting was agreed for each indicator, policy cluster, and dimension through a complex process, which resulted in each country being awarded a score between 1 and 100. For a country to score 100, their drug policy and practice would need to be aligned with the recommendations contained in the UN documents mentioned above.2,3

In this first iteration, the GDPI focuses on 30 countries, selected based on criteria including geographical location, availability of data on drugs and drug policy, and the presence of civil society organisations that could use the Index without fear of reprisal.5 Ireland is not among those included. The European countries represented are Hungary, Norway, Portugal, Russia, and the United Kingdom (UK).

Source: The Global Drug Policy Index 2021, p. 29

SAG: Scientific Advisory Group

Figure 1: GDPI five-step methodological process

Scope of the GDPI

The Index is made up of 75 indicators that run across five dimensions:

- The absence of extreme sentencing and response to drugs, such as the death penalty

- The proportionality of the criminal justice response to drugs

- Funding, availability, and coverage of harm reduction interventions

- Availability of international controlled substances for pain relief

- Development.

Results

In addition to ranking the countries, the report identifies seven key takeaways from the Index.

1 The global dominance of drug policies based on repression and punishment has led to low scores overall, with a median score of just 48/100, and the top-ranking country (Norway) only reaching 74/100. The authors argue that most countries’ drug policies are misaligned with their governments’ obligations to promote health, human rights, and development, hence the relatively low scores (see Figure 2).

2 Standards and expectations from civil society experts on drug policy implementation vary from country to country. Given the role of civil society in providing the evidence on the implementation of a country’s drug policy, the authors reflect on how this may impact on the scoring of some indicators.

3 Inequality is deeply seated in global drug policies, given their greater emphasis on human rights, harm reduction, and health. The five top-ranking countries scored three times as much as the five lowest-ranking countries. The authors attribute this in part to the colonial legacy of the ‘war on drugs’ approach.

4 Drug policies are inherently complex. A country’s performance in the Index can only be fully understood by looking across and within each of the dimensions. The authors note that a country’s performance in one dimension of drug policy may not necessarily mirror how well they are doing in another. They highlight the case of the UK, which has the highest score (84/100) on avoiding police abuses, arbitrary arrests, and detentions, and ensuring fair trial rights, but is one of the lowest-ranking countries regarding experts’ perception of the disproportionate impacts of the criminal justice response on women, marginalised ethnic communities, and low-income groups.

5 Drug policies disproportionately affect people marginalised because of their gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. In addition, the Index underscores how people who use drugs continue to be discriminated against by drug policies across the world.

6 There are wide disparities between what is written in national drug policies and how they are implemented on the ground. These disparities are particularly apparent in the areas of health (e.g. access to harm reduction interventions), decriminalisation, and alternatives to prison and punishment.

7 With a few exceptions, the meaningful participation of civil society and affected communities in drug policy processes remains severely limited.

Source: The Global Drug Policy Index 2021, p. 34

Figure 2: Highest-ranking and lowest-ranking countries in the GDPI

1 Nougier M and Cots Fernández A (2021) The Global Drug Policy Index 2021. London: Harm Reduction Consortium. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/35122/

2 United Nations System Chief Executives Board for Coordination (2018) United Nations system common position supporting the implementation of the international drug control policy through effective inter-agency collaboration, CEB/2018/2. New York: United Nations. Available online at: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/35818/

3 UN System Coordination Task Team on the Implementation of the UN System Common Position on Drug-related Matters (2019) What we have learned over the last ten years: a summary of knowledge acquired and produced by the UN system on drug-related matters. Vienna: United Nations. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/30372/

4 Members of the Harm Reduction Consortium are as follows: the European Network of People who Use Drugs (EuroNPUD); the Eurasian Harm Reduction Association (EHRA); the Eurasian Network of People who Use Drugs (ENPUD); the Global Drug Policy Observatory (GDPO) at Swansea University; Harm Reduction International (HRI); the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC); the Middle East and North Africa Harm Reduction Association (MENAHRA); the West Africa Drug Policy Network (WADPN); the Women and Harm Reduction International Network (WHRIN); and Youth RISE. For further information, visit: https://globaldrugpolicyindex.net/about

5 This first edition of the Index covers 30 countries from all regions of the world: Afghanistan, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Georgia, Ghana, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco, Mozambique, Nepal, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Norway, Portugal, Russia, Senegal, South Africa, Thailand, Uganda, and the United Kingdom. This list will be expanded in future iterations of the Index.

Repository Staff Only: item control page