Dillon, Lucy (2021) Evaluation of Targeted Response with Youth. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 79, Autumn 2021, pp. 47-49.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 79)

1MB |

Targeted Response with Youth (TRY) is a peer-mentoring project based in Dublin's south inner city, which targets young people involved in or at risk of becoming involved in the drug economy and antisocial behaviour (ASB). An evaluation of the programme was published in November 2020, entitled Relentless caring: trying something new.1

Meeting a need

The project is based in and around St Teresa’s Gardens (STG), a local authority complex in Dublin’s south inner city. The area has high levels of early school leaving, unemployment, poor mental and physical health outcomes, crime, and drug use. Under the Pobal HP Deprivation Index, it was categorised as ‘very disadvantaged’, the lowest score on the scale.2 Ongoing regeneration of the STG complex has meant that many tenants were moved elsewhere, leaving residences empty to facilitate new builds. The report argues that ‘as a consequence of detenanting STG, a small group of marginalised, hostile and “extremely threatening” young men with external addresses but family ties in STG made it their daily stomping ground for ASB and drug-related activity, negatively impacting the quality of life of residents’ (p. 16). Recourse to control tactics, such as prosecution and imprisonment or the threat of eviction for those living elsewhere, had failed to address the community’s needs. In addition, the young people causing the problems were considered hard to reach. A stakeholder described them as ‘extremely marginalised people who are not liked in the community and people do not want to work with them’ (p. 27). The lack of appropriate services to address the complex needs of these young people, and the consequences of their behaviour, led to the establishment of TRY.

Delivery model

Based on the experiences of national and international projects, TRY uses the intensive outreach and bridging (IOB) model.3 Youth workers contact the targeted young people at street level, build trust, and provide them with emotional and practical support. There is a focus on building their self-esteem and other positive traits to enable them to extend their social networks beyond those associated with the drugs economy. In addition, the project encourages and facilitates young people to engage with services, depending on their needs. Services accessed include those related to education or work pathways, physical or mental health services, housing, and childcare facilities. Engagement takes place on a one-to-one basis and through group work.

Target group

When it started in 2017, the project targeted a group of young men (aged 18–24 years) who were engaged in ASB, including drug-related activity, in and around STG. The project subsequently expanded to include young women and those under the age of 18. Between October 2019 and September 2020, TRY worked with 37 young people: 22 males (aged 18–24), 13 females (aged 18–24), and two under-18s (aged 14–17) (p. 41).

Method of evaluation

The evaluation involved a literature review, documentary analysis, and qualitative interviews with a variety of stakeholders (n=19). Participants were mainly those involved in the delivery and governance of the project. Only two local residents and two TRY participants were interviewed. Interviews were recorded and thematic analysis carried out on the data. No additional detail on the sampling, fieldwork or analytical approaches was provided in the report.

Findings

Childhood adversity

Young people participating in the project tended to have experienced one or more of a wide range of childhood adversities, including domestic, physical, and emotional abuse; familial drug addiction; parental incarceration; community violence; and family bereavements. It was identified as a ‘major problem’ (p. 28) that these traumas were often not discussed, which stakeholders described as leading to much anger among the young people. This was thought to have contributed to other service providers finding them challenging, hard to reach, and difficult to engage.

Central role of mentor relationship

Central to the success of the project is the relationship that mentors develop with the young people. A high level of trust must be built between the two, which takes time and persistence on the part of the mentor. The author argues that the mentor must be ‘authentic, believable, caring and kind’ (p. 24) with the relationship being built through intensive outreach. There also needs to be ‘exceptional levels of professionalism [on the part of the mentor] to appear to be involved in casual conversation but to actually have a careful professional agenda’ (p. 31), through which the young person’s needs are identified and bridging to appropriate services takes place. Staff also need a high degree of flexibility to deliver interventions at locations and times required by the young people. It was deemed critical that mentors have similar life experiences to participants and come from the same type of background.

Structured assessment

Mentors use various tools to add structure to how they work with young people. For example, they use a goals scale to highlight the gaps in a beneficiary’s life and to help them visualise and set achievable goals. They also use a logic model to determine what referrals need to be made and to support their bridging role.

Bridging

As the relationship between the mentor and young person develops, new needs frequently emerge. Additional needs often relate to mental health, parenting skills, anger management, and a desire to access addiction treatment services. Close collaboration between mentors and other service providers to meet the young people’s needs is critical. Mentors act as a bridge between the two and provide ongoing support to the young people to maintain attendance. This includes attending appointments with the young person.

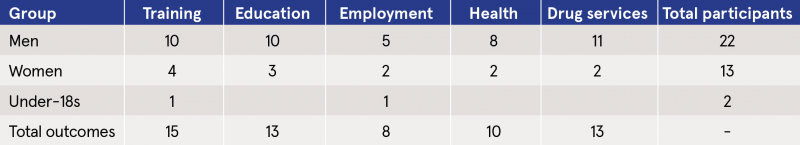

Table 1: TRY project outcomes October 2019–September 2020 (Sláintecare Integration Fund interim report)

Source: Mulcahy (2020) p. 41

Outputs and outcomes

From October 2019 to September 2020, the total number of contacts made with individuals was 1,552 (p. 27), where the breakdown of referrals made to services in 2020 was: 22% to education/training; 24% drug intervention; 7% housing; 19% employment; 9% social welfare/money; and health services 19% (p. 36). The report includes examples of young people’s confidence building and of taking up opportunities to further their education, enter employment, and access other services to meet their health needs. Table 1 summarises the outcomes reported by the project for 2019/20.

Cost effectiveness

While no value-for-money analysis was carried out, the author does compare the costs of TRY (approximately €100,000 in 2019) with those of punitive criminal justice responses. The cost of detaining one young person in Oberstown Children Detention Campus is €383,574 and of imprisoning an adult is €75,349. She concludes that ‘in terms of criminal justice savings alone, the TRY project since its inception [2017] has been very good value indeed’ (p. 23).

Concluding comment

The findings echo those of an earlier more comprehensive piece of work published in 2019 by Bowden, notably The drug economy and youth interventions: an exploratory research project on working with young people involved in the illegal drugs trade.4,5 While the TRY evaluation provides useful insights into the TRY project and the value of mentoring for this cohort of young people, it is also limited. A key limitation is that only two project participants took part. It is important that young people’s voices are heard in evaluations of programmes that affect them. Without this, there can only be a limited assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of a programme as regards for whom it works well and why. However, the key messages from Bowden’s report4,5 remain relevant here:

- Engaging with people who are involved in drug distribution is not about excusing their behaviour, rather understanding it with the aim of prevention.

- Any engagement needs to be structured around a strong relationship with an advocate, characterised by trust and understanding.

- Young people involved in the drug economy or at risk of getting involved are reachable. If there were viable educational and employment pathways open to them, many would desist from the drug economy.

1 Mulcahy J (2020) Relentless caring: trying something new. An evaluation of the Targeted Response with Youth TRY project. Dublin: Donore Community Drug and Alcohol Team.

https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/34556/

2 The Pobal HP Deprivation Index shows the degree of overall affluence and deprivation at the level of electoral division using data compiled from the Irish Census.

3 National and international IOB projects include the Easy Street project of Ballymun Regional Youth Resource (BRYR), Dublin and the Lugna Gatan (Easy Street) model in Sweden. For further information, visit: http://www.bryr.ie/ and https://www.bra.se/download/18.cba82f7130f475a2f1800026910/1371914734658/2002_examination_of_lugna_gatan.pdf

4 Bowden M (2019) The drug economy and youth interventions: an exploratory research project on working with young people involved in the illegal drugs trade. Dublin: CityWide Drugs Crisis Campaign.

https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/30487/

5 Dillon L (2019) The drug economy and youth interventions. Drugnet Ireland, 70 (Summer): 12–14. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/31007/

L Social psychology and related concepts > Interpersonal interaction and group dynamics > Social support

MM-MO Crime and law > Criminality > Youth (juvenile) offending

MM-MO Crime and law > Crime deterrence

T Demographic characteristics > Adolescent / youth (teenager / young person)

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page