Dillon, Lucy (2021) Alcohol pricing and marketing: policy actions from WHO. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 76, Winter 2021, pp. 8-11.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet 76)

1MB |

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Regional Office for Europe has published reports on the evidence and recommended policy actions for reducing the harm caused by alcohol via its pricing and marketing regulations.1, 2 The reports are intended to be a resource for governments and those implementing policies across Europe.

Background

Both reports are grounded in the context of Europe having per capita the highest levels of alcohol consumption, the highest prevalence of heavy episodic drinking, and the lowest rates of abstention from alcohol of any region in the world. In turn, it is estimated that more than one in every 10 deaths in Europe is caused by alcohol consumption.3 The reports reflect two of the 10 priority areas for action to address these harms, as identified in the WHO European Action Plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol 2012–2020; and subsequently two of the four priority areas in the 2020 report on the consultation on strengthening the implementation of the WHO’s action plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol.4 The pricing and marketing of alcohol are identified as policy areas for which there is ‘very strong evidence that such measures are effective’ in reducing alcohol-related harm

(p. 5).4

Alcohol pricing

Alcohol pricing in the WHO European Region1 summarises the current evidence base for alcohol pricing policies and how this compares with the policies currently in place across the region. Based on the current evidence, the authors argue that increasing the prices that consumers pay for alcohol is one of the most effective tools available to policymakers looking to reduce alcohol consumption and associated harm. Pricing policies have also been found to be cost-effective, especially when the cost savings to healthcare and other public services are taken into account. There is a range of pricing policy options outlined in the report, some of which are found to be more effective in addressing alcohol-related harms and socioeconomic health inequalities than others. Specific taxation linked to inflation and minimum unit pricing (MUP) are the approaches found to be the most effective.

Taxation

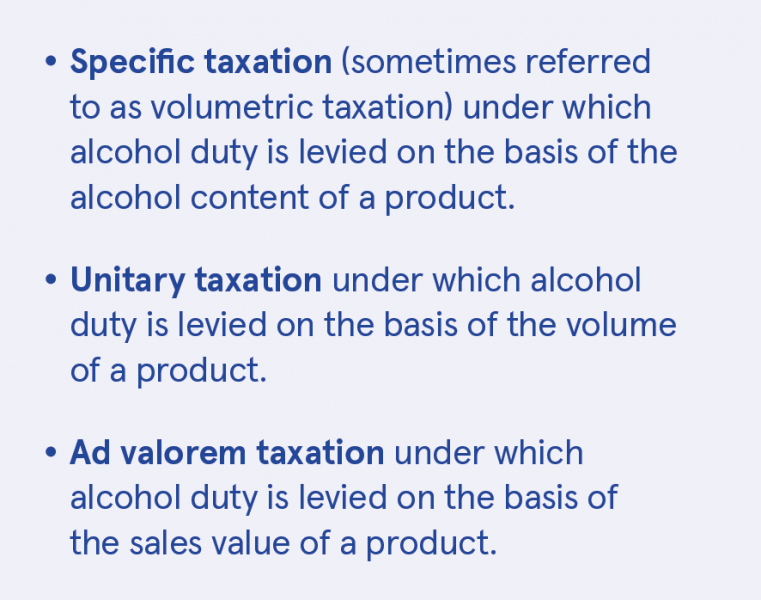

Alcohol taxation is identified as the primary mechanism through which governments can influence alcohol prices. There are three ways in which taxation can be applied to alcohol: specific, unitary, and ad valorem (see Box 1). The evidence shows that the best approach from the perspective of improving public health and tackling health inequalities is through specific taxation, by which the tax payable on a product is directly proportional to its alcoholic content. It is argued that the different types of alcohol products (e.g. beer, wine, spirits) should have similar tax rates to avoid a scenario where heavy drinkers are encouraged to drink larger volumes of particular products because they are subject to a lower rate of tax and therefore cheaper. However, where products have low production costs relative to other types of alcohol, it can be justified to apply higher taxes to prevent these products being available to consumers at lower prices. To maximise the positive impact of this pricing strategy, alcohol taxes should also be linked to inflation to prevent the affordability of alcohol increasing over time.

Box 1: Three main approaches to alcohol taxation

Source: Alcohol pricing in the WHO European Region: update report on the evidence and recommended

policy actions, Box 2, p. 3

Minimum unit pricing

MUP attracted a lot of attention in Ireland in the course of passing the Public Health (Alcohol) Act 2018. MUP has a robust evidence base of being effective in reducing alcohol and consumption, especially among the heaviest drinkers. It introduces a floor price below which a fixed volume of alcohol (e.g. a unit or standard drink) cannot be sold to the public. While taxation affects the price of all products, MUP only increases the price of the cheapest alcohol. Since heavier drinkers typically favour cheaper drinks, MUP policies effectively target price increases at heavier drinkers without significantly affecting the prices of alcohol bought by moderate drinkers, who tend not to seek out the cheapest products. The report highlights the finding that MUP is particularly effective in addressing the health inequalities stemming from alcohol-related harm by targeting cheap, high-strength products.

Other pricing policies

Other pricing policies explored in the report are found to be relatively rarely implemented across the WHO European Region. These include applying restrictions or a ban on:

- The sale of alcohol at below the cost the retailer paid for it – ‘loss leaders’

- The sale of alcoholic products for less than the cost of the tax payable on the product

- The discounting of products by alcohol retailers

- Multibuy discounts.

Implementation

The report found that despite the clear evidence in favour of a specific tax system that is indexed to inflation, no country in the WHO European Region has fully implemented this. MUP is also not widely used across the region. The report maps out each country’s approach to pricing policies. Ireland’s basis of taxation (excluding VAT) is identified as specific for beer and spirits and unitary for wine, and that MUP is pending. Logistical and legal barriers are identified to implementing the preferred approach, as well as strong opposition from the alcohol industry. Even where they might wish to implement a fully specific system of alcohol taxation, member states of the European Union (EU) are prevented from doing so. There are EU directives that require wine and other products, including cider, to be taxed on a unitary basis. The report concludes that these restrictions mean that EU countries are unable to implement tax systems that are optimal from the perspective of public health. The report argues for the revision of these directives as a priority for public health.

Alcohol marketing

Alcohol marketing in the WHO European Region2 finds that ‘research has shown a correlation between exposure to alcohol advertising and drinking habits – in particular, between youth exposure to alcohol marketing and initiation of alcohol use – and clear associations between exposure and subsequent binge or hazardous drinking’ (p. ii).2 As a policy response to this correlation, the regulation of alcohol marketing has been found to be a cost-effective strategy to reduce alcohol-related harm and is recommended by WHO. The report explores the regulation of the marketing of alcohol products in the region.

Implementation of policies

The report finds that most European countries have implemented policies regulating alcohol advertising, especially that which reaches children and young people. These policies range from complete bans with penalties for legal offences to self-regulatory codes of conduct adopted by industry. Research is cited showing that the self-regulatory codes are limited in terms of their effectiveness in regulating the alcohol industry’s activities. While countries vary in their policies, Ireland is one of three countries identified in the report as having the protection of young people most explicitly and effectively taken into consideration through their policymaking.

Changing landscape for marketing

Central to the report2 is the changing landscape of the media being used in the marketing of alcohol products and the challenges this presents to regulators. Consumers (including children and young people) are being targeted by marketing messages not just from the traditional channels of television and print media, but also through the internet (particularly through social media) via quickly evolving digital marketing methodologies. The report outlines the ways in which this is happening and draws on research into food brands and how they use digital media to target children and young people.

Digital media have changed the nature of alcohol marketing and the report outlines the complexities that this change presents. For example:

- Those marketing alcohol products not only create their own content but also tap into user-generated content to market their products, which means the boundaries between advertiser and consumer become blurred.

- Research has found that the sharing of content on social media communities that includes alcohol in some way increases the cultural acceptance of alcohol use among members of these communities.

- There are increased difficulties associated with monitoring the age of users and their exposure to alcohol-related content.

Recommended policy options

While the report makes a set of recommendations on how to develop a policy response in an environment characterised by the increasing use of digital marketing methodologies, this environment presents increasing challenges from a legislative and regulatory point of view. The five policy options (Box 4, p. 14)2 identified are:

- WHO suggests that bans or comprehensive restrictions on alcohol advertising are one of the top three most effective and cost–effective interventions to address the harmful use of alcohol. Digital marketing should be included in such regulatory frameworks.

- If a complete ban is not feasible, partial statutory restrictions on the content of posts published online should be implemented. In this case, sufficient resources should be earmarked for active supervision and robust enforcement of policies. As thousands of posts are published on a multitude of platforms daily, this is an extensive, yet

crucial task. - There is an urgent need to develop a protocol to help distinguish between native advertising, user-generated content and other commercial messages that may be difficult to understand or interpret. The real senders of such material are likely to be invisible to consumers, especially young consumers and children.

- As many young people participate in social media milieus as a natural part of their everyday life, the very least a jurisdiction should do is to demand that alcohol brands properly enforce age verification (age-gating). Implementation of age limits on (for example) Facebook and Instagram pages is technically a small and straightforward matter. This is the least that should be expected to protect children and teenagers, and to ensure that underage users do not gain access to alcohol-related posts.

- Member states should take a consistent stance on the legal obligation of marketers to accurately tag media content and ensure that inappropriate content does not reach children.

1 World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe (2020) Alcohol pricing in the WHO European Region: update report on the evidence and recommended policy actions. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/32286/

2 WHO Regional Office for Europe (2020) Alcohol marketing in the WHO European Region: update report on the evidence and recommended policy actions. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/32341/

3 World Health Organization (2018) Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/29701/

4 WHO Regional Office for Europe (2020) Final report on the regional consultation on the implementation of the WHO European Action Plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol (2012–2020). Prague, Czech Republic, 30 September–1 October 2019. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/32587/

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Policy > Policy on substance use

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Marketing and public relations (advertising)

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Economic policy

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Economic aspects of substance use (cost / pricing)

VA Geographic area > International

Repository Staff Only: item control page