Galvin, Brian (2018) Drugs and the darknet: new EMCDDA report. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 65, Spring 2018, pp. 13-16.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland, Issue 65 Spring 2018)

- Published Version

2MB |

Two-thirds of sales on darknet markets are drug related. These anonymous online markets enable transactions with neither buyer nor seller having to reveal anything about their identify. So-called ‘cryptomarkets’ are a relatively new phenomenon but the opportunity they present to undermine conventional law -enforcement approaches inevitably means that they will be a driver of significant growth in criminal activities over the next few years. A recent EMCDDA publication, Drugs and the darknet: perspectives for enforcement, research and policy1 presents an analysis of drug-related activity on darknet markets, focusing on specific European countries and also looking at the phenomenon from the perspective of law enforcement agencies required to monitor and counter the operation of these markets.

In 2017, Europol identified the online trade in illicit goods and services as a key growth area for organised crime.2 Darknet markets are websites that allow anonymous financial transactions. Access to these markets can be through ordinary, surface websites providing addresses for darknet sites; through surface mirror sites with links to hidden sites; or through invitation following reference from an existing user. The key technologies supporting these markets are anonymisation services, encrypted communication and cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin or Dogecoin. Users seeking to make illicit sales can use a search engine, Grams, specially designed for this purpose. Innovative use of instant messaging for communication and social media applications with GPS (global positioning systems) technologies presents particular difficulties for surveillance and regulatory work. In addition, many darknet markets offer their customers an escrow service with a multisignature function and the guarantee that the goods paid for will be delivered.

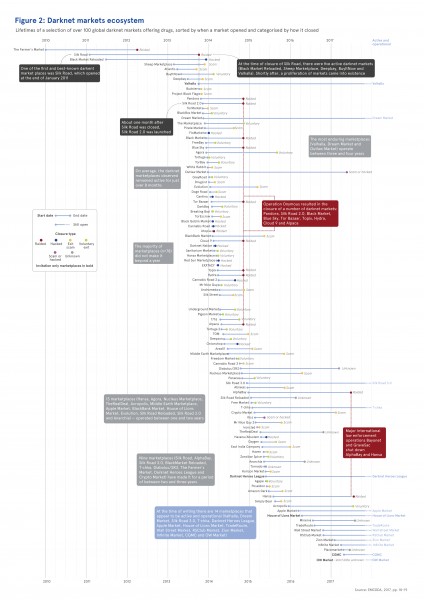

The first of these cryptomarkets was Silk Road, closed down by American law enforcement agents in 2013. Since then, an estimated 100 darknet markets have been created, many of which only operate for a short time. At the time of the EMCDDA report being written, there were an estimated 14 darknet markets operating. Despite the methodological and practical difficulties of researching darknet markets, a number of studies have provided useful data and at least highlight areas that will need further investigation and monitoring. Much of this work has focused on the behaviour and experience of those purchasing drugs online. Demographic characteristics were consistent across a number of studies with young, student or professional males with a history of drug use being the most common type of users in the limited samples observed. Personal safety and drug quality were the most frequently cited considerations when choosing to use online sources for drugs. While the purity of drugs purchased online does vary, a limited number of studies do show that what is ordered online will subsequently be delivered, and that those who purchase online usually find the suppliers are reliable. Websites use facilities such as marketplace feedback and rating polls to build confidence in their reliability and the quality of the products they supply. Researchers have used feedback data as a source of information in studying darknet activity.

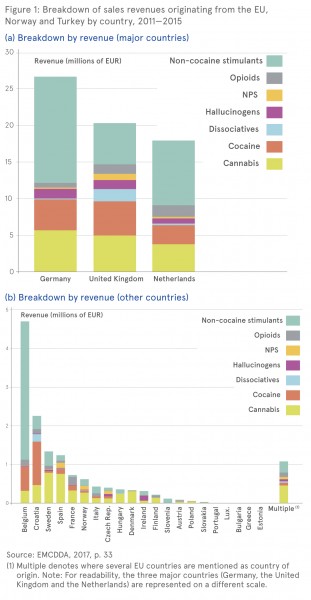

The report looks at the findings of a 2015 study that sought to gain a better understanding of the extent of darknet drugs sales originating from Europe.3 Based on data gained from buyer feedback reports, the study estimated the volumes and value of drugs traded over a period of about three and half years. The data suggest that the vast majority of sales originating from the EU during this period were from three countries: Germany (€26.6 of sales); the United Kingdom (UK) (€20.2m of sales); and the Netherlands (€17.9m of sales). The most common substances sold in the top four countries (including Belgium) were non-cocaine stimulants, principally MDMA and amphetamines. Cannabis and cocaine sales were also significant in the sales from these countries, while the UK-based sites were far more likely to sell dissociatives and new psychoactive substances. In terms of drug sales, EU countries represent roughly 46% of global revenue. A more detailed 2017 study of AlphaBay2, one of the most important darknet marketplaces and active for about two years, shows that the vast majority of drugs sales originated from the same three countries identified in the 2015 study.

Analysis of sales data shows that vendors tend to confine their activity to one market level: retail, middle or wholesale. In other words, very few vendors are involved in both bulk and small volume sales. While the majority of these vendors operate at the lower market level, it is estimated that just 1% of vendors are responsible for more than 50% of darknet sales. These sellers are connected to organised crime gangs and make considerable profits. Law enforcement authorities expect online markets to take an increasing share of the overall illicit drug market and may even replace the use of traditional distribution networks among some user demographics. The EMCDDA report describes darknet markets as ‘tailor-made polycriminal environments’, as they allow criminal groups to distribute a wide range of illicit commodities, with no restriction on the type of drugs they trade in online. The increasing professionalism of darknet markets suggests to law enforcement observers that criminals involved in distributing drugs via street dealers are increasingly using darknet market trading as an additional distribution channel and revenue stream. Law enforcement actions such as taking down major marketplaces have only a short-term effect, as both vendors and customers will move to alternative sites or new darknet markets will emerge.

In 2014, the European Court of Justice ruled that retention of data by internet service providers for law enforcement purposes was no longer legal, a ruling that has been interpreted and implemented differently in EU member states. Though its ultimate impact is uncertain, the ruling has reduced the ability to effectively prosecute online criminal activity. While international legislative instruments do exist, differences with domestic law often impede criminal investigations with an international dimension. An additional difficulty is the sometimes cumbersome nature of international cooperation, which often slows the investigative process, an important consideration in gathering electronic evidence. While a sustainable response to illegal online markets will require a significant increase in cybercrime expertise, a number of more traditional responses have been reasonably effective, including monitoring of postal and parcel deliveries.

Drug sales account for around two-thirds of all cryptomarket transactions reviewed. Effective responses to cybercrime require the same technological ability and innovative thinking as that displayed in criminal practice. This study provides the conceptual framework necessary to understand developments in this area. It includes an EU-focused analysis of darknet operations and of the challenges faced by law enforcement in responding to it. Market disruption needs to form part of an integrated set of measures, including identifying and targeting major vendors, dealing with key elements in the supply chain, and the development of responses that are technologically informed, coordinated and collaborative. Implementation of this response will require increased investment to support specialist investigation capacities. There needs to be pooling of resources at the European level to coordinate activities across jurisdictions, especially in light of recent judicial decisions. A framework for improving criminal justice in cyberspace is set out in the recent European Council conclusions4.

There are significant knowledge gaps around the darknet trade in drugs, especially regarding the actors and mechanisms not apparent through observation of online transactions. Currently, very little is known about the sources of drugs supplied on darknet markets or how the supply chain is organised. It is also important to get a better understanding of what makes buying and selling online attractive and why online behaviour changes according to region. Potential further threats include development of decentralised software and new encryption technologies; changes in parcel delivery services; integration of local markets with online markets; and greater concentration on national online markets to avoid customs detection. Future software developments may allow websites to be hosted across several servers, countering current responses that involve targeting specific servers. This development, combined with innovative use of social media, instant messaging and GPS, may enable a highly efficient drug distribution network linked to local markets undermining existing markets and posing greater challenges to law enforcement. As yet, this remains a potential threat, but it underlines the importance of systematic monitoring of anonymous online activity.

1 European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) and Europol (2017) Drugs and the darknet: perspectives for enforcement, research and policy. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/28246

2 Europol (2017) European Union Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment (SOCTA): crime in the age of technology. The Hague: Europol. Available at:

3 Soska K and Christin N (2015) Measuring the longitudinal evolution of the online anonymous marketplace ecosystem. In Proceedings of the 24th USENIX Security Symposium, Washington DC, 12‒14 August 2015, pp. 33‒48. Available online at: https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/usenixsecurity15/sec15-paper-soska-updated.pdf

4. Council of the European Union (2016a), Council conclusions on improving criminal justice in cyberspace of 9 June 2016, doc. 10007/16 (www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/jha/2016/06/cyberspace-- en_pdf).

MM-MO Crime and law > Organised crime

MM-MO Crime and law > Substance related offence > Drug offence > Illegal distribution of drugs (drug market / dealing)

MM-MO Crime and law > Justice and enforcement system

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Marketing and public relations (advertising) > Internet retailing (online sales / dark web)

N Communication, information and education > Digital technology

VA Geographic area > International

Repository Staff Only: item control page