Millar, Sean (2017) Audit of hepatitis C testing and referral, 2015. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 63, Autumn 2017, p. 32.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 63)

1MB |

In 2014/15, an audit was carried out in Ireland of hepatitis C (HCV) testing and referral in Addiction Treatment Centres in Health Service Executive (HSE) Community Health Organisation (CHO) Area 7 (formerly HSE Dublin Mid-Leinster). CHO Area 7 covers Dublin 2, 4 (part of), 6, 6W, 8, 10, 12, 16 (part of), 22 and 24. The audit was not carried out in the satellite clinics or in West Wicklow and Kildare as services there are in community-based general practice. The number of patients attending the addiction treatment centres in CHO 7 at the time of starting the audit was 1,255.

The purpose of this audit was to inform the Audit Sub-Group of the Addiction Treatment Clinical Governance Committee of CHO 7 of compliance with the expected standard of care in relation to HCV, and to make recommendations for improvement where necessary. A secondary aim of the study was to collect and collate data on the prevalence of HCV infection in this sample of patients.1

Methods

A customised audit form was developed. One form was to be completed for each patient attending the centre. Data were requested on age, gender, and whether or not the patient was tested for HCV. Risk factors for infection, co-infection with HIV, referral to a specialist clinic (hepatology or infectious diseases), attendance at a specialist clinic and what level of treatment, if any, was provided were also requested. No personally identifiable information was collected on patients. In order to encourage cooperation and to avoid making comparisons between centres, the form did not contain the name of the doctor or the treatment centre.

A letter accompanied by the audit form was sent to 20 GPs in 11 addiction treatment centres in CHO 7 outlining the audit project and requesting their assistance in completing the forms. A total of 319 audit forms were returned, representing 25% of the patients attending the services at that time. It was not possible to determine how many doctors or treatment centres participated, as the study was anonymous. The main findings from this audit are outlined below.

Findings

Age and sex

Where data were available, 63% (198/315) of the population were male and the age range was 24—65 years. The median age for males was 38 years, while the median age for females was 36 years. The majority of patients (81%) were between the ages of 25 and 44 years.

Risk factors for HCV infection

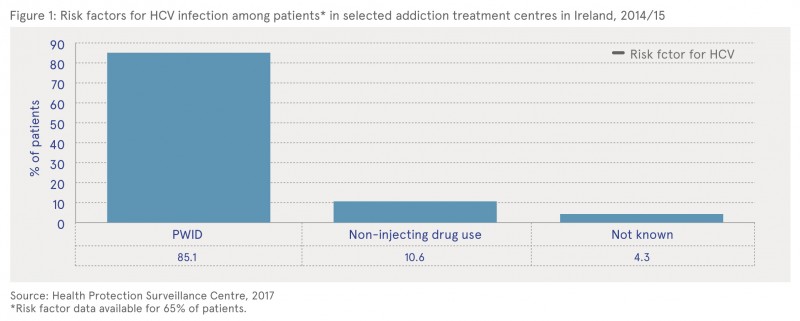

Information on possible risk factors for infection was available for 65% (208/319) of patients (Figure 1). Of these patients, 85.1% (177/208) had a history of injecting drug use (people who inject drugs — PWID), 10.6% (22/208) had non-injecting drug use risk factors and 4.3% (9/208) had no known risk factor. Of those with non-injecting drug use risk factors, 17 reported cocaine use, 4 reported unprotected sex with a HCV positive person, and 1 reported both cocaine use and unprotected sex with an HCV positive person.

Of the 177 patients who had a history of injecting drug use, 72% (128) were HCV antibody positive and 44% (78) were HCV antigen or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positive. In those with HCV antigen or PCR positive results, the age range was 24—56 years, with a median age of 40 years. The likelihood of having HCV increased with age in those with a history of injecting drug use, with 63% (10/16) of 25—34-year-olds testing positive for HCV antigen or PCR compared to 68% (45/66) of 35—44-year-olds and 80% (20/25) of 45—54-year-olds. Data on HCV testing were available for 14 patients, of whom 5 were positive for HCV antibodies. Two of these 5 patients were also HCV antigen or PCR positive.

HIV infection

HIV status was recorded on 242 patients, of whom 39 (16%) were HIV positive. The median age of HIV positive patients was 39 years (range 31—56 years). Of these, 37 were also HCV antibody positive; 20 of these were HCV antigen or PCR positive. The majority (70%) of those co-infected with HIV were male. Where data were available, 97% (34/35) of all HIV positive patients were reported to have a history of injecting drug use. Overall, 19% (34/177) of those with a history of injecting drug use were HIV positive.

Referral and attendance at hepatology or infectious diseases clinics by gender

Where data were available, 86% (88/102) of HCV antigen or PCR positive patients were referred to a specialist clinic and, of those, 66% (52/79) attended. Males were more likely than females to attend a specialist clinic following referral, with a 74% (39/53) attendance rate, compared to just 50% (13/26) of females. The likelihood of attendance at a specialist clinic also increased with age, with just 36% (4/11) of those in the 25—34-years age group having attended following referral, compared to 68% (30/44) of 35—44-year-olds and 76% (16/21) of 45—54-year-olds.

Treatment uptake and completion

Data were collected on whether or not treatment was offered, accepted, completed and successful in antigen positive patients. Out of 105 patients who tested positive for the HCV antigen or PCR, data were available on offer of treatment for 57 patients. Of those, 28 patients (49%) were recorded as having been offered treatment and 29 were not offered treatment. Of the 28 patients who were offered treatment, 6 were awaiting treatment at the time of audit, 3 were still in treatment, 4 had refused treatment, 7 had completed treatment and there was no further information on the remaining 8 patients. Of the 7 patients who had completed their treatment, it was successful in 4, and no information was provided on the remaining 3 cases.

Conclusions and recommendations

One aim of this audit was to provide information on the current prevalence of HCV infection in patients attending addiction treatment clinics in Ireland. Two-thirds (67%) of patients who had been tested were positive for HCV antibodies. This figure is in keeping with previous studies in Ireland among PWID, which found the prevalence to be 62% to 81%.2 The prevalence was slightly higher (72%) in those with a recent history of injecting drug use. The prevalence of HCV markers was higher in older patients, which may reflect their longer injecting history and opportunity for exposure to HCV, or may indicate a reduction in incidence in recent years.

Data from nationally collated notifications of HCV infection show a substantial downward trend in notifications, and rising age at diagnosis, since peak levels in 2007.3 However, it must be borne in mind that, given the overall low response rate to this audit, the findings may not be representative of the population of patients attending addiction treatment services in this region, or in Ireland.

The following were among the recommendations suggested by the authors to further understand infectious disease prevalence among drug users in Ireland:

- A computerised-patient management system for addiction treatment clinics is urgently needed. This would improve the efficiency of the clinics and make better use of staff resources, and would improve quality of care for patients.

- The under-resourcing of clinics is an ongoing cause for concern and should continue to be highlighted on the HSE Risk Register.

- Improved communication from specialist hospital clinics to the referring doctors in the addiction treatment clinics regarding patients who have been offered treatment would be helpful to patient care. In particular, it would be useful for the referring doctor to have timely information on uptake of treatment and response to treatment, and also to know if the patient has refused treatment. The HCV liaison nurses may have a role to play in improving this information flow.

- Individual doctors and clinics should be supported in maintaining compliance with HCV testing and referral.

- Attendance at specialist hepatology and infectious diseases clinics, particularly for younger patients, should be encouraged by referring doctors and by the HCV liaison nurses. The reasons for poor attendance should be investigated.

- Addiction treatment doctors and HCV liaison nurses have a role in educating patients about the risks and prevention of blood-borne virus transmission, and about the availability of new antiviral treatments.

In addition, the authors recommend that the audit should be repeated. It was suggested that the next audit should explore the practices in relation to retesting those patients who initially test HCV negative but have ongoing risk-taking behaviour. It should also seek to gather more detailed information about treatment uptake and outcome. A repeat study would be helpful to indicate if recently observed increases in the incidence of HIV infection in drug users has been mirrored by a rise in HCV infection. It is hoped that the circulation of this report may encourage a better response rate for the next audit. A better response would allow for more confidence in the representativeness of the findings and more clearly indicate opportunities for improvement.

1 Bourke M, Hennessy S, Thornton L (2015) Audit of hepatitis C testing and referral: Addiction Treatment Centres, Community Health Organisation Area 7. Lenus, the Irish Health Repository. Available online at https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/28118/

2 Health Service Executive (2012) National hepatitis C strategy 2011—2014. Dublin: Health Service Executive. Available online at https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/18325/

3 HSE — Health Protection Surveillance Centre (2015) Annual epidemiological report 2014: hepatitis C. Dublin: Health Service Executive. Available online at https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/28119/

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Harm reduction > Substance use harm reduction

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Health related issues > Health information and education > Communicable / infectious disease control

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Patient / client care management

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page