Dillon, Lucy (2017) Headshop legislation and changes in national addiction treatment data. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 62, Summer 2017, pp. 13-14.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet issue 62)

700kB |

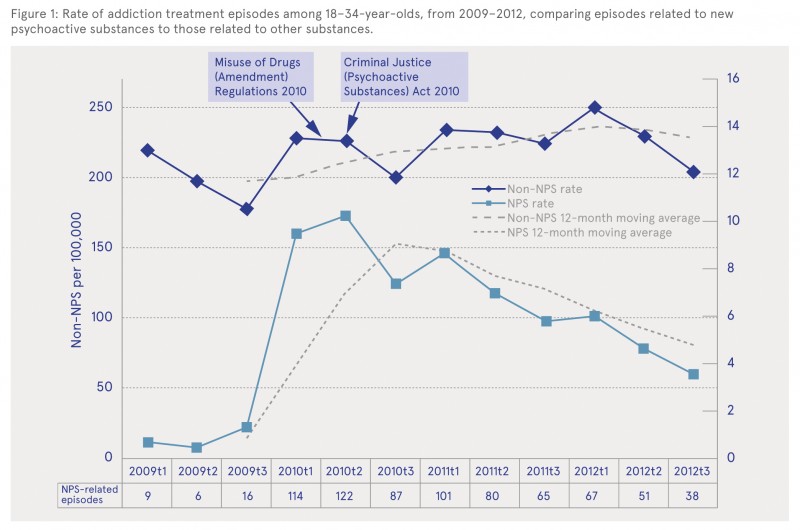

A new paper by Smyth et al. explores the relationship between changes in legislation related to new psychoactive substances (NPS) and their problematic use.1 In 2010, new psychoactive substances (NPS) were the subject of two new pieces of legislation in Ireland. The first (enacted in May 2010), expanded the list of substances controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1977−1984 to include over 100 NPS.2 The second, the Criminal Justice (Psychoactive Substances) Act 2010 (enacted in August), differed from the established approach to drug control under Ireland’s Misuse of Drugs Act, in that it covered the sale of substances by virtue of their psychoactive properties, rather than the identity of the drug or its chemical structure. It was aimed at vendors of NPS and effectively made it an offence to sell a psychoactive substance.3 This ‘two-pronged legislative approach’ was largely in response to an increase in the number of so-called ‘headshops’ selling NPS from late 2009 to a peak of 102 premises in May 2010. By October 2010, only 10 headshops were still open and by late 2010 the Gardaí indicated that none of the remaining shops were selling NPS.

Legislative bans such as these have attracted debate internationally as to their effectiveness in impacting on the overall availability and use of NPS, in particular problematic use.4 Smyth et al. explored whether ‘the arrival and subsequent departure of the headshops coincided with changes in presentation of problem NPS use among adults attending addiction treatment services in Ireland’.

Methods

The paper is based on analysis of data from the National Drug Treatment Reporting System (NDTRS), an epidemiological database on treated drug and alcohol misuse in Ireland.5 It collects self-reported information on service users’ main problem drug and up to three additional problem drugs. Problem drug use is ‘generally understood [in the NDTRS] to equate to dependence or harmful use as described in ICD-10’. The system does not use a unique patient identifier and therefore the units of analysis reported on in the paper were treatment episodes, except where analysis focused on the cases of those never previously treated for drug use. A treatment episode was considered to be NPS-related, where a NPS was identified as a ‘main’ or ‘additional’ problem drug. A range of statistical analyses were carried out on the data, including odds ratios and jointpoint regression (further detail is available in the paper). To reflect the timeline of changes in problem NPS use in Ireland and the introduction of the relevant legislation, the paper examined episodes of treatment recorded in the NDTRS between 2009 and 2012 at four-month intervals.

Key findings

Key findings included that:

- NPS use can cause substance use disorders and create treatment demand. In what Smyth et al. called ‘the headshop era’ (i.e. January−August 2010), 4.2% of treatment episodes among 18‒34-year-olds were NPS-related. This was compared to 2.4% of treatment episodes for the same age group over the three-year period 2009‒2012.

- Between 2009 and 2012, the NPS group had a higher proportion of males when compared to the non-NPS group and had a younger age profile. The median age of the NPS group was 25 years compared to 35.6 years for the non-NPS group.

- A decline in treatment episodes for NPS followed the enactment of the second piece of legislation that effectively ended ‘the headshop era’ in August 2010. The rate of NPS-related treatment episodes increased rapidly from the period September to December 2009, through early 2010, and peaked between May and August 2010. It decreased progressively after that point (see Figure 1). Smyth et al. highlighted that the rate of NPS-related treatment episodes did not just ‘plateau’ following the enactment of the legislation causing the headshops to close,rather it ‘declined progressively by almost 50%’ over the subsequent two years.

- Similar changes were not found for non-NPS related treatment episodes over the same time period (2009‒2012).

- While there was an overall decrease in NPS treatment episodes after August 2010, where they did occur, NPS stimulant powders accounted for an increased proportion of them, while the proportion of NPS cannabis-like substances declined.

- The rate of NPS-related treatment episodes declined more acutely among young people who had never before sought addiction treatment, when compared to overall treatment episodes.

- An NPS was the main problem drug in 39% of NPS-related treatment episodes in 2010, but this fell to 16% in 2012. Therefore, even though NPS continued to feature in treatment episodes after the headshops had closed, they were more likely to be a ‘peripheral problem’.

[Figure 1 ]

While acknowledging other possible explanations, the authors note that their findings ‘are consistent with a hypothesis that the legislation and consequent closure of the headshops contributed to a reduction in NPS-related substance use disorders in Ireland’. They concluded that:

While policy responses based on prohibition type principals appear to have fallen out of favour globally in the past decade, the experience of Ireland’s response to NPS suggests that such policies remain a legitimate component of society’s response to this complex and ever-changing challenge.

However, more recent data from the NDTRS show that NPS use is still problematic in Ireland and is showing a slight increase. While reported use of an NPS as a main drug of problem use among all age groups peaked in 2010, at 2.5% of all cases treated, and dropped to 0.4% of all cases treated in 2012, since then it has increased slightly to represent 0.9% of all cases treated in 2015.6

1 Smyth BP, Lyons S and Cullen W (2017) Decline in new psychoactive substance use disorders following legislation targeting headshops: evidence from national addiction treatment data. Drug and Alcohol Review, early online. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/27172/

2 Misuse of Drugs (Amendment) Regulations 2010. Available online at http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2010/si/200/made/en/pdf

3 Criminal Justice (Psychoactive Substances) Act 2010 (commencement) Order 2010. Available online at http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2010/si/401/made/en/pdf

4 Dillon L (2016) New psychoactive substances: legislative changes in the UK. Drugnet Ireland, 59: 9−10. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/26231/

5 For further information on the NDTRS, visit: http://www.hrb.ie/health-information-in-house-research/alcohol-drugs/ndtrs/

6 Health Research Board (2017) Drug treatment in Ireland NDTRS 2009−2015. Dublin: Health Research Board. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/27023 and http://www.hrb.ie/publications

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Treatment and maintenance > Treatment factors

L Social psychology and related concepts > Legal availability or accessibility

MM-MO Crime and law > Substance use laws > Drug laws

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page