Millar, Sean (2017) Injecting drug use and hepatitis C treatment. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 63, Autumn 2017, p. 25.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 63)

1MB |

People who inject drugs (PWID) represent the majority of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) epidemic in the developed world.1 The majority of new infections develop in active PWID, with this group accounting for more than 80% of new infections in high-income countries.2 Furthermore, an additional large reservoir of infection exists among former PWID who remain undiagnosed.

Historically, HCV treatment guidelines have excluded PWID from consideration for treatment. Drug injectors are viewed as having ‘difficult to treat’ HCV disease, with perceived inferior treatment adherence and outcomes, and concerns regarding reinfection risk. Important factors that have limited treatment uptake in PWID are the contraindications and adverse effects of interferon (IFN) based therapy. The development and availability of IFN-free direct acting antiviral (DAA) regimes with high efficacy, improved tolerability and a limited side-effect profile will significantly increase the proportion of patients who can be offered HCV therapy. However, adherence to therapy in ‘real world’ population groups will remain paramount in the DAA era.

A recent study conducted in Ireland investigated differences in HCV treatment adherence and outcomes between former PWID, recent PWID, and non-drug users treated with IFN and ribavirin therapy.3 In this study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, differences between PWID and non-drug users were analysed for adherence to treatment and outcomes in all patients treated for chronic HCV infection in a university teaching hospital from 2002 to 2012. The PWID group also included former and recent drug users who were treated in a community-based drug treatment centre.

Results

Treatment completion/compliance

There were 608 former PWID, 85 recent PWID, and 307 non-PWIDs who commenced HCV therapy. There was no significant difference in treatment non-completion (for reasons other than virologic non-response) between PWID and non-PWIDs (8.4% vs 6.8%, relative risk: 1.23, 95% CI: 0.76–1.99). Additionally, there was no significant difference in treatment non-completion between former and recent PWID (8.7% vs 5.9%, relative risk: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.33–2.10). Fifteen patients (17.6%) in the recent PWID group tested positive for opiates at least once during treatment, 11 (12.9%) tested positive for benzodiazepines, and 5 (5.8%) tested positive for cocaine. Seven patients tested positive for two of the drug classes, while 5 tested positive for all three classes. No patients reported injecting illicit drugs during treatment or in the 6-month post-treatment follow-up period.

Response to treatment

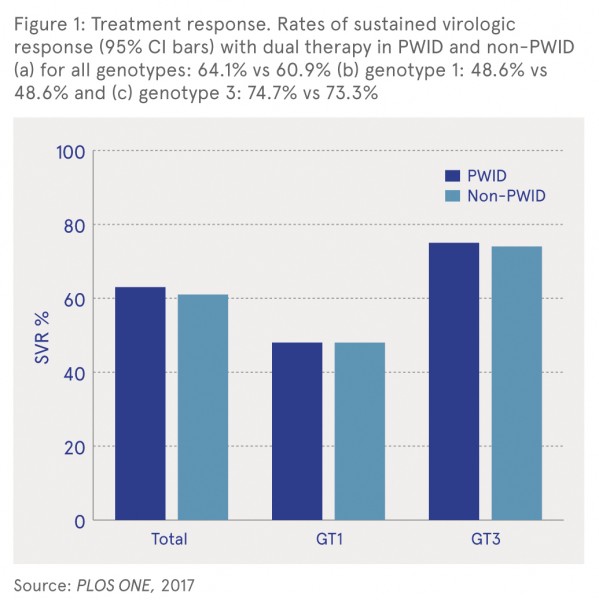

As shown in Figure 1, the overall sustained virologic response (SVR) rate in PWID (64.1%) was not different from non-PWIDs (60.9%) (relative risk: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.95–1.17). In addition, there was no significant difference in SVR rates between the groups when comparing genotype (GT) 1 and genotype 3 infections.

Follow-up data on 219 former PWID who achieved SVR between 2002 and 2007 for a median of 57 months (range 6–168 months) indicated that 13 patients were reinfected with HCV, a reinfection rate of 10.5/1000 person years of follow-up. All 13 patients had a relapse in injecting drug use. There was no significant difference in reinfection rate between former PWID with and without HIV co-infection.

Conclusions

The results from this large retrospective study of a decade of HCV treatment outcomes indicate that PWID have similar treatment adherence to IFN and DAA HCV therapy as non-PWID patients with chronic HCV infection. In addition, PWID patients have a comparable response to treatment. The authors concluded that prioritising PWID for HCV treatment may be a more cost-effective initiative for reducing long-term health costs and that HCV elimination is an ambitious target that cannot be achieved by excluding PWID from treatment.

1 Nelson PK, Mathers BM, Cowie B, Hagan H, Des Jarlais D, Horyniak D and Degenhardt L (2011) Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. Lancet, 378: 571—83. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/15845/

2 Cornberg M, Razavi HA, Alberti A, Bernasconi E, Buti M, et al. (2011) A systematic review of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Europe, Canada and Israel. Liver International, 31: 30—60. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/27691/

3 Elsherif O, Bannan C, Keating S, McKiernan S, Bergin C and Norris S (2017) Outcomes from a large 10 year hepatitis C treatment programme in people who inject drugs: no effect of recent or former injecting drug use on treatment adherence or therapeutic response. PLOS ONE, 12(6): e0178398. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/27486/

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Harm reduction > Substance use harm reduction

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Health related issues > Health information and education > Communicable / infectious disease control

T Demographic characteristics > Person who injects drugs (Intravenous / injecting)

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page