Long, Jean (2015) Alcohol pricing model applied to Ireland. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 54, Summer 2015, pp. 3-5.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 54)

1MB |

In 2013 the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group (SARG) at Sheffield University was commissioned by the Irish government to adapt the Sheffield pricing model for alcohol to Ireland in order to appraise the potential impact of different pricing policies. The report was published on 11 March 2015.1 Some key findings from the report are presented here.

Minimum unit pricing (MUP)

The first question posed was ‘What are the effects of introducing a legislative basis for minimum pricing per 10 grams of alcohol or per standard drink, i.e. minimum unit pricing (MUP), in Ireland over a 20-year period?’ To answer this question, a pricing model was applied that used a simulation framework based on classical econometrics and cost-benefit analysis techniques. The methods are described in detail in the report.

Two effects of interest are described here – alcohol consumption and individual spending. The effects of interest were examined by drinker type – low-risk, increasing-risk and high-risk.

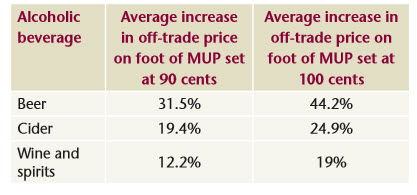

Prices of standard drinks

Prices vary by type of beverage. The evidence suggests that the impact of a potential minimum price of 90 cents or 100 cents for a standard drink will be greatest on beer, with average off-trade price increases of 31% and 44% respectively, followed by cider, with average increases of 19% and 25% respectively. The lowest increases will be for wine and spirits, which will rise by an average of around 12% and 19% respectively (see Table 1).

Alcohol consumption

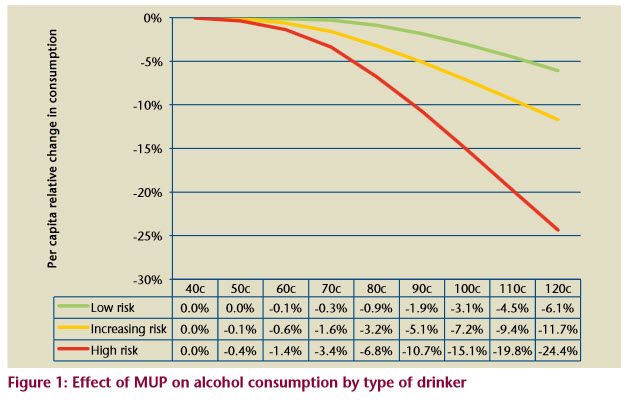

MUPs below 70 cents are estimated to have a very small impact on alcohol consumption (see Figure 1). However, Figure 1 also shows how alcohol consumption across the overall population starts to reduce when the MUP is set at 70 cents or higher (80c = -3.8%; 90c = -6.2%; 100c = -8.8%; 110c = -11.7%).

For a 100c MUP, the estimated per-drinker-reduction in alcohol consumption for the overall population is 8.8% and equates to an average annual reduction of 57.2 standard drinks per drinker per year. As this is a targeted pricing policy, high-risk drinkers have larger estimated reductions in alcohol consumption as a result of an MUP policy than increasing-risk or low-risk drinkers. For example, the estimated reductions in consumption for a 100c MUP are 15.1% for high-risk drinkers, 7.2% for increasing-risk drinkers and 3.1% for low-risk drinkers (see Figures 1 and 2). These reductions correspond to an annual reduction of 494 standard drinks per year for high-risk drinkers, 83.2 standard drinks for increasing-risk drinkers and 5.2 standard drinks for low-risk drinkers.

Individual spending

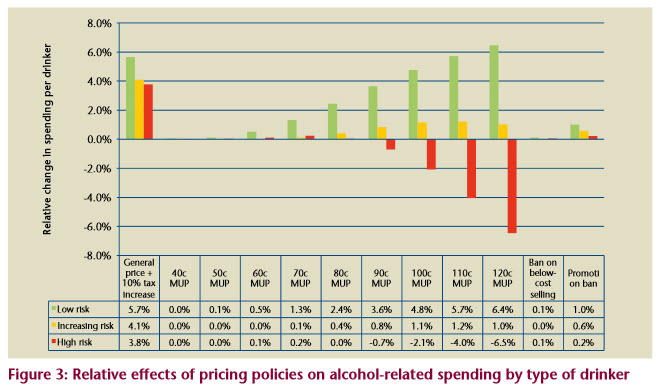

Under an MUP policy, drinkers are estimated to reduce consumption but pay somewhat more on average for each standard drink consumed, and so the estimated percentage changes in spending are smaller than estimated changes in consumption (see Figure 3). The MUP policies are estimated to have small impacts on overall alcohol–related expenditure, for example expenditure will increase by 1.3% at 90c and 100c MUP, and 1.1% at 110c MUP.

For a 100c MUP, the estimated per drinker change in alcohol expenditure for the overall population is 1.3% and this equates to an average annual increase of €15.70. As this is a targeted pricing policy, high-risk drinkers will save €106.60 (-2.1%) each year as a result of an MUP policy, while increasing-risk drinkers will spend an extra €25.40 (1.1%) per year on alcohol and low-risk drinkers will spend an additional €24.20 (4.8%).

Value to society

For a 100c MUP policy, the total societal value of the harm reductions for health, crime and workplace absences is estimated at €1.7bn cumulatively over the 20-year-period modelled. This figure includes reduced direct healthcare costs, savings from reduced crime and policing, savings from reduced workplace absences and a financial valuation of the health benefits measured in terms of Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) valued at €45,000, in line with guidelines from the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics on the cost-effectiveness of health technologies.

MUP and other pricing policies

In addition to understanding the impact of MUP in an Irish context, the Irish government wanted to know ‘How does MUP compare to, or enhance, other pricing policies?’ Specifically, how does MUP compare to, or enhance, other measures such as a ban on price-based promotions in the off-licence trade, a combination of MUP policies with a ban on price-based promotions, a ban on below-cost selling and a 10% price rise on all alcohol products.

Ban on promotions

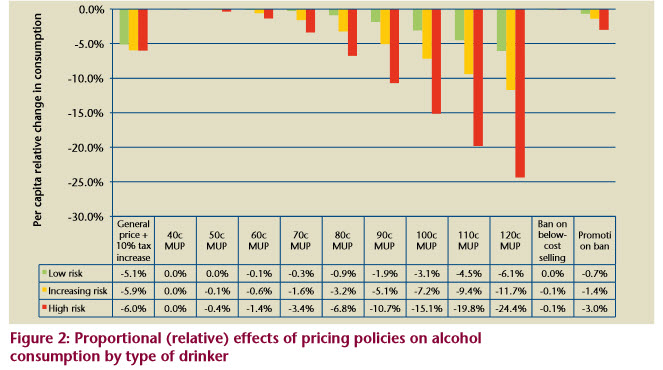

Banning all price-based promotions in the off-trade is estimated to reduce per-person alcohol consumption by 1.8%. As this is a targeted pricing policy, high-risk drinkers have larger estimated reductions in alcohol consumption as a result of an MUP policy than increasing-risk or low-risk drinkers. For example, the estimated reductions are 3% for high-risk drinkers, 1.4% for increasing-risk drinkers and 0.7% for low-risk drinkers (see Figure 2).

Under a promotions ban on trade retailers, drinkers are estimated to reduce consumption but pay somewhat more (0.6% or €7.20 each year) for alcohol consumed. As this is a targeted pricing policy, high-risk drinkers will spend an additional €11.40 (0.2%) each year as a result of the promotions ban while increasing-risk drinkers will spend an extra €13.00 (0.6%) on alcohol and low-risk drinkers will spend an additional €5.10 (1%) (see Figure 3).

Over the 20-year period modelled, the total societal value of the harm reductions resulting from a ban on promotions is estimated to be €0.38bn. This societal value equates to one-third that of a 90c MUP.

Ban on below-cost selling

A ban on below-cost selling is estimated to have minimal positive or negative impact on population consumption (see Figure 2), spending (see Figure 3), health outcomes and crime. It would save a cumulative €38.4m over 20 years.

Overall tax increase

The introduction of a 10% (tax) increase on the price of all types of alcohol (cheap and expensive) would decrease alcohol consumption for all drinkers by 5–6% and would affect low-risk, increasing-risk and high-risk drinkers equally (see Figure 2). It would have health benefits as well as reducing crime and workplace absences. The total societal value of the harm reductions arising from a general price increase over the 20-year period modelled is estimated at €1.6bn cumulatively.

- Angus C, Meng Y, Ally A, Holmes J and Brennan A (2014) Model-based appraisal of minimum unit pricing for alcohol in the Republic of Ireland. University of Sheffield: ScHAAR. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/23904/

B Substances > Alcohol

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Economic policy

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Economic aspects of substance use (cost / pricing)

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

Repository Staff Only: item control page