Pike, Brigid (2015) How does Ireland’s drugs policy compare with others? Drugnet Ireland, Issue 53, Spring 2015, pp. 4-5.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland 53)

2MB |

Two studies comparing the drug policies of different European countries, including Ireland, have recently been published. One compares the ‘governance’ of addictions across the member states of the EU and Norway, and the other examines the ‘coherency’ of policies on psychoactive substances (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) across seven member states of the Council of Europe.

The governance of addictions

This comparative assessment was undertaken by ALICE RAP (Addictions and Lifestyles in Contemporary Europe – Reframing Addictions Project), a European research project, co-financed by the European Commission.1 ALICE RAP’s assessment was premised on the argument that addictions inflict an excessive burden not only on individuals but also on societies as a whole. Moreover, in the 21st century, Western societies are being forced to adjust their policies to new realities which include a growing diversity of consumption scenarios, their progressive normalisation in some contexts and even their trivialisation in others. The comparative assessment sought to discover, to what extent do the policies of different member states respond to the new and emerging circumstances.

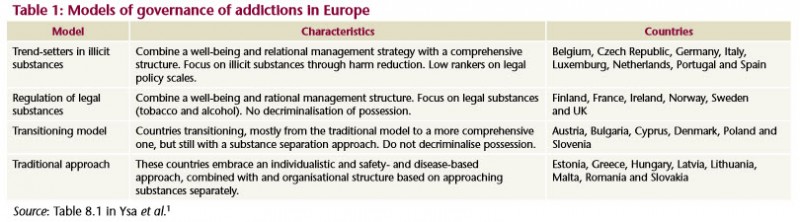

The authors used ‘strategy’ and ‘structure’ to analyse similarities and differences (the degree of ‘convergence’) between member states’ addiction policies. They asked a question in relation to each of these two dimensions of governance, linking them to the content of the policy and the extent to which individual member states are pursuing a ‘traditional’ as opposed to more innovative approaches.

- Strategy: To what extent does the strategy adopt a ‘safety-and-disease’ focus or display a wider interest in ‘relational management of well-being’ across society as a whole?

- Structure: What substances are included in the strategy, and does it expand beyond misuse of addictive substances to encompass addictive activities such as gambling?The authors identified four clusters of countries, reflecting four different models of ‘governance of addictions’. Ireland is deemed to be in a handy enough position but is not among Europe’s ‘trend-setters’ (Table 1).

The authors see the first model – ‘Trend-setters in illicit substances’ – as the model towards which all countries should aspire. This model is characterised mainly by its strategy for illicit substances, giving considerable importance to harm reduction policies such as needle exchanges and injection rooms. Another distinguishing characteristic is that all eight countries linked with this model decriminalise possession of illicit substances.

With regard to the six countries linked to the second model, including Ireland, the authors see these countries as having developed ‘a regulatory approach to licit substances and loose measures to combat illicit substances’. They attribute these two separate trajectories to the heavy consumption of alcohol in these jurisdictions. The authors also note that these are the six countries in the sample that use evidence-based regulation on alcohol and tobacco, but that only the United Kingdom consistently implements best-practice interventions. Moreover, the countries associated with model 2 do not implement as many innovative policies as the countries associated with model 1, and neither are they as proactive.

With regard to ‘structure’, the countries linked with model 2 are all classified as having a comprehensive policy-making structure, tending to combine legal and illicit substances, involving non-profit organisations in decision-making, having an ad hoc co-ordinating body, decentralising implementation, and having a long history of legislating for illicit substances. The authors conclude that these countries, including Ireland, could build on their comprehensive structure and their well-being and relational management approach, by extending it towards illicit substances (see Figure 1).

Coherency of policies on psychoactive substances

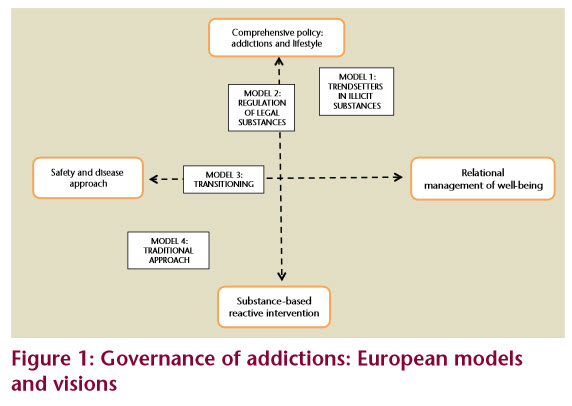

The second comparative assessment, undertaken by the Council of Europe’s Pompidou Group, whose mission is to contribute to the development of multidisciplinary, innovative, effective and evidence-based drug policies in member states, similarly found that Ireland is in a handy enough position, but is not at the forefront, in relation to the coherency of its policies on different psychoactive substances, namely illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco.2 The assessment comprises a series of case studies; the authors of each case study assessed the coherency of the policies in their country in relation to the World Health Organization’s overarching population-based health goal – ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.

The case study on Ireland shows that, of the three national policies on psychoactive substances, tobacco is the one most consistently aligned with a population-based approach to health. Two initiatives that will shift alcohol policy in Ireland closer to a population-based approach are noted: (1) in 2012 the National Substance Misuse Strategy Steering Committee published its report, calling for a population-based approach to alcohol misuse, and (2) in 2013 the first public health bill in Ireland to focus on alcohol measures was being drafted. At the time of going to press, however, neither initiative had been fully implemented. The case study reports a population-based approach in the planned response to problematic drug use. However, because of the criminal activity, public disorder, anti-social behaviour and violence that may be associated with illicit drugs, criminal justice responses have been adopted as well. While these latter measures may achieve the desired criminal justice outcomes, the report observes that they undermine the move towards a population-based approach to health by criminalising and/or stigmatising problem drug users (see Figure 2).

The case study on Ireland concludes:

This continuing lack of coherence among policies on various psychoactive substances, particularly alcohol and illicit drugs, in relation to an over-arching population-health objective, may be expected to hinder the realisation of ‘a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ among the Irish population. (p. 189)

1 Ysa T, Colom J, Albareda A, Ramon A, Carrion M and Segura L (2014) Governance of addictions: European public policies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. For more information on ALICE RAP, visit http://www.alicerap.eu.

2 Muscat R, Pike B and members of the Coherent Policy Expert Group (2014) Coherence policy markers for psychoactive substances. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. http://www.coe.int/T/DG3/Pompidou/default_en.asp

3 For an explanation of how the spider diagram was compiled, see Pike B (2014) New ‘policy tool’ supports transparency and open debate. Drugnet Ireland (52): 28 https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/23318/

Repository Staff Only: item control page