Garavan, Carrie and Long, Jean and Lyons, Suzi (2014) Prevalence of drug use and blood-borne viruses in Irish prisons, 2011. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 50, Summer 2014, pp. 7-11.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet issue 50)

2MB |

Background

The National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol (NACDA) has published the results of a survey estimating the extent of drug use and the prevalence of blood-borne viruses among the prison population in Ireland.1 The survey questionnaire was completed by a random sample of prisoners between February and April 2011. Oral fluid samples were obtained to assess use of specific drugs (cannabinoids, opiates, methadone, cocaine and benzodiazepines) in the 24 to 72 hours preceding the survey and to detect the presence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV infections. Flexibility was required in different prisons to accommodate prison schedules, security arrangements and prisoner availability.

Of the 1,666 randomly selected prisoners, 824 took part in the study, giving a response rate of 49.5%, which is much lower than that achieved in previous Irish prison studies2-4 and lower than that required for a robust prevalence estimate. Completed questionnaires and oral fluid analysis were available for 46% (771/1,666) of invited participants. Of the 886 prisoners who attended the information session, 7% (62) declined to participate in the study. Field workers reported that reasons given by 47% (780) of prisoners for not attending the information session included unavailability, attendance at the gym, school or workshop, mistrust, suspicion, cynicism, apathy, and concerns regarding mandatory drug testing and DNA sample collecting.

Most respondents were male (95%) and Irish (92%). The average age was 31 years, and 50% were aged 28 years or under. Almost one-in-four respondents (23%, 186) received no schooling or primary education only compared to one-in-five of the general population in Ireland and only 13% (105) reported having some third-level or completed third-level education compared to 31% in the general population. Sixty per cent (483) had been in custody for more than one year, and 52% (419) had spent more than three of the past ten years in prison. More than one in ten had been homeless for more than seven days in the year before the survey. More women (46%) than men (22%) reported that they had been homeless in the 12 months prior to the survey.

This article summarises four key areas addressed in the report:

- prevalence of drug use among prisoners;

- prevalence of injecting drug use;

- prevalence of blood-borne viral infection; and

- prison drug treatment and harm-reduction services.

Prevalence of drug use

Lifetime prevalence (ever used)

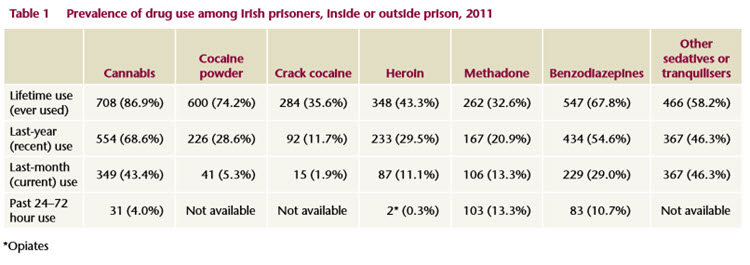

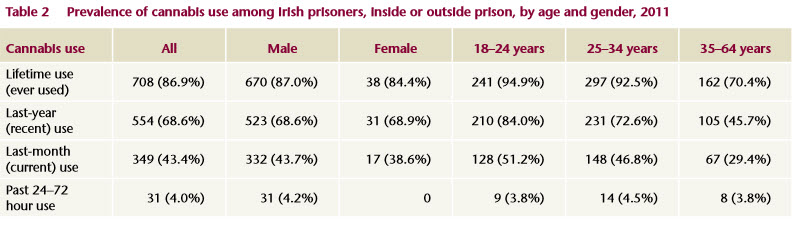

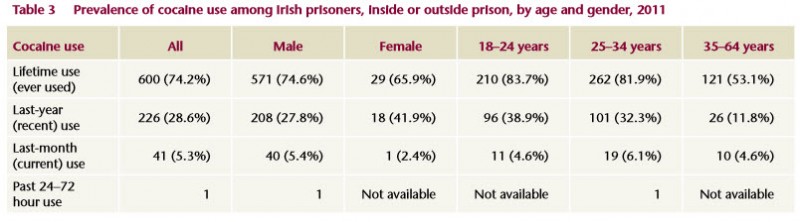

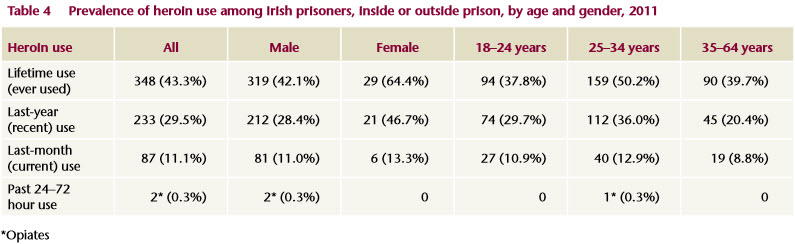

The drugs most commonly used among the prison population were cannabis (87%) cocaine powder (74%) and benzodiazepines (68%) (Table 1). There was no difference between men’s and women’s lifetime use of cannabis, cocaine or benzodiazepines (Tables 2-5). Lifetime heroin use was high at 43% (Table 4). Women were significantly more likely than men to use heroin (64%), methadone (60%) and crack cocaine (59%) at some point in their life (Tables 2-5). It is important to note that some of the methadone and benzodiazepine use was prescribed, and most of the illicit drug use occurred outside the prison environment.

Last-year prevalence (recent use)

Cannabis, at 69%, was the drug most commonly used in the year prior to the survey, followed by benzodiazepines, at 55% (Table 1). The 25–34-year-olds were significantly more likely to have used heroin (36%) compared to the older (20%) or younger (30%) age groups (Table 4). Of those who had used a drug in the last year, a majority in each case had used the drug while in prison: 88% had used cannabis; 85% benzodiazepines; 87% other sedatives or tranquillisers; 87% methadone; 84% heroin; 66% other opiates; and 52% crack cocaine.

Last-month prevalence (current use)

Cannabis (43%) was the drug most commonly used in the past month, followed by benzodiazepines (29%). One-hundred-and-three prisoners (13%) tested positive for methadone in the 24 to 72 hours prior to the survey and 106 reported being prescribed methadone daily in the last month. Eighteen per cent of those who tested positive for methadone were in the 25–34-year age group. Women were significantly more likely to test positive for methadone than men (33% v 12%).

Use in previous 24–72 hours

Oral fluid sample testing for drug use in the previous 24–72 hours found that proportionally more women than men were on daily methadone maintenance. Four per cent (n=31), all men, had used cannabis in the 24–72 hours before the survey, and 11% (n=83) had used benzodiazepines. Women (20%) were two times more likely to test positive for benzodiazepine use than men (10%).

Methods of heroin use

Two-hundred-and-twenty-six prisoners said they were ’doing heroin now’ t. Seventy-five per cent of current heroin users reported smoking (or chasing the dragon) as their only method of choice, with 13% reporting injecting and 1% snorting as their only method. Only a very small proportion (1.3%) currently used all three methods of administration. The proportion of those who smoked and snorted was 1.3%, whereas 9% both smoked and injected.

Prescription drug use in prison

High usage of benzodiazepines and other sedatives and tranquillisers, and of methadone and other opiates was reported by participants. The vast majority (85%) of prisoners who reported taking methadone in prison in the month prior to the survey had taken it on prescription. A minority of prisoners had taken benzodiazepines (14%) and other sedatives (22%) under medical supervision (or on prescription). A large proportion reported having taken unprescribed benzodiazepines in prison in the previous month.

Prevalence of injecting drug use

Lifetime prevalence (ever injected)

Over 26% reported having ever injected drugs, with women (44%) more likely to have a lifetime history of injecting drug use than men (24%). Thirty-four per cent of the 25–34-year age group were more likely to have injected than their older (22%) or younger counterparts (18%). The most common drug injected was heroin (19%), followed by cocaine powder (13%). Women were more likely than men to have injected heroin (43% vs 18%), cocaine powder (32% vs 12%), mephedrone (16% vs 4%), methylone (11% vs 2%) and any other drug (14% vs 4%).

Last-year prevalence (recent injectors)

The most commonly injected drug in the last year was heroin (7%), followed by cocaine powder (3%), benzodiazepine (3%) and steroids (2%). More women than men had injected heroin (21% vs 6%), cocaine powder (14% vs 3%), mephedrone (13% vs 2%), methylone (7% vs 1%), amphetamines (7% vs 1%) and benzodiazepines (11% vs 2%), with no significant differences across age groups.

Last-month prevalence (current injectors)

The numbers reporting injecting in the last month were low (1 to 8 people injecting each drug). Cocaine powder was injected by eight respondents (1%), heroin by seven (0.9%), benzodiazepines by four (0.5%) and steroids by four (0.5%).

Age at first use of drugs

Fifty per cent of cannabis users had used it by their 14th birthday. Half of all benzodiazepines users had used it by their 17th birthday. The median age for first use of cocaine powder was 18 years, and for heroin 19 years. Among heroin injectors, the average length of time between moving from smoking to injecting heroin was 2.8 years. The median age for commencing injecting head shop drugs such as methylone and mephedrone was 24 years, and for steroid injecting 22 years.

First use and first injection

Of those who reported having ever used heroin (smoking or injecting), 146 (43%) said they had taken it for the first time in prison and these were more likely to be men (46%) than women (17%). Twenty-one per cent of women and 6% of men (8% overall) who had ever injected heroin reported having injected it for the first time in prison. Of the 69 who had started injecting in prison, 16 (24%) injected steroids while 12 injected heroin.

Of injectors who had injected in the past year, 13 of the 19 recent steroid injectors had injected in prison, 9 of 56 recent heroin injectors had done likewise, as had 7 of 23 recent benzodiazepine injectors and 7 of 25 recent cocaine injectors.

Prevalence of blood-borne viral infection

Risk factors for viral infection reported by prisoners were:

- Sharing injecting paraphernalia: Of those who reported having ever injected drugs and answered the questions on sharing equipment, 48.8% (84/172) shared needles, 49% (81/165) syringes and 52% (84/162) other injecting equipment. A greater proportion of females (78%) reported sharing needles and syringes compared to males (46%).

- Sexual behaviour: Self-reported rates of unprotected sex (having sex without a condom) were high both while in prison (62%) and outside prison (51%). Less than 2% of men reported that they had ever had sex with other men (1.5% outside prison and 0.9% in prison).

- Tattooing: More than two-thirds (68%) of participants had borstal or tattoo markings, and 35% had had a tattoo done in prison.

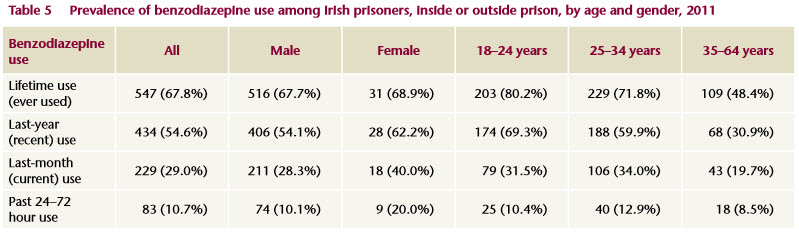

Hepatitis C prevalence: oral fluid test

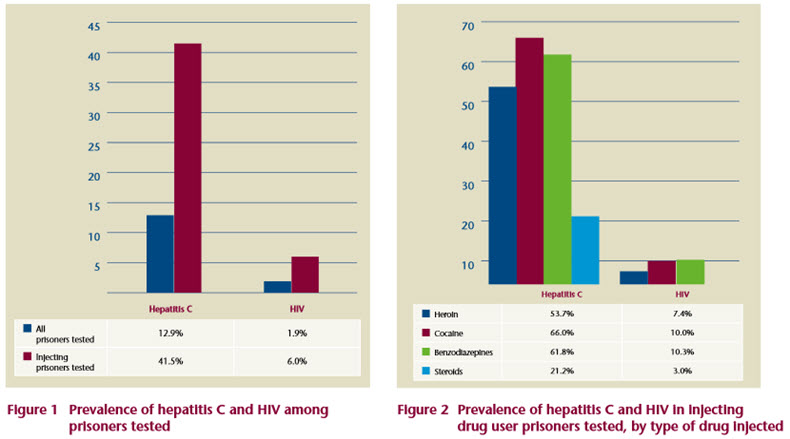

The overall prevalence of hepatitis C was 12.9% among the prisoners tested, and 41.5% (83/200) among those who were injecting drug users (Figure 1). Prevalence of hepatitis C varied with the type of drug injected; the rates of positive test results were: 54% (80/149) of heroin injectors , 66% (66/100) of cocaine injectors, and 62% (42/68) of benzodiazepine injectors, and 27% (14/66) of steroid injectors (Figure 2). The prevalence rate in the Irish population has been estimated at 0.5-1.2%5 – much lower than the rate experienced by either prisoners or injecting drug users.

A previous study reported a prevalence rate for hepatitis C of 37% among prisoners and 81% among injectors; however, these were mainly heroin injectors.2

The concordance analysis revealed that 21 (9%) of those who thought they were negative had a positive test result and three (1%) of those who reported being positive had a negative test result.

Multivariate analysis indicated that five factors were associated with hepatitis C infection: being female, being over 25 years old, having a history of injecting drug use, sharing injecting equipment and having had tattoos done in prison.

Hepatitis B prevalence: oral fluid test

The prevalence of hepatitis B was 0.3% among the prisoners tested. The prevalence of hepatitis B in the general population in Ireland is low (< 1%).6

A previous prison study found prevalence rates for hepatitis B of 9% among prisoners and 18.5% among injectors in prison.2 The introduction of blood-borne viral testing and hepatitis B vaccination in the Irish Prison Service in 1995 accounts for the reduction of hepatitis B infection among drug users in prison.

The concordance analysis indicated that eight people (3%) think they have a disease that they do not have and one person (0.4%) has a disease that he does not know he has and may not be taking the necessary precautions to prevent spread of infection to others.

HIV prevalence: oral fluid test

Fifteen participants tested positive for HIV, resulting in a prevalence of 1.9% among prisoners and 6.0% among injecting drug users in prison (Figure 1). Figure 2 presents the prevalence of HIV among injecting drug users by type of drug injected and demonstrates that the prevalence of HIV is between 7% and 10% among hard drug users. The Irish population prevalence is estimated to be 0.2% (15–49-year- olds).7

In a previous Irish prison study, prevalence of HIV was 2% among all prisoners and 3.5% among injectors.2

The concordance analysis revealed three (1.4%) people who thought they were negative were positive and one (0.4%) prisoner who thought he was positive was negative.

While the numbers who tested positive for HIV were small (15/657), four factors were found to be associated with HIV infection: being female, having a history of injecting drug use, sharing injecting equipment, and male-to-male sexual contact.

Steroid injectors

Of note, there were 69 self-reported steroid injectors, of whom 16 had started to inject in prison and 13 had injected in prison in the last year. Fourteen steroid injectors tested positive for hepatitis C and two for HIV. This study identifies a new cohort of injecting drug users and hepatitis C infection.

Co infection: oral fluid test

Fourteen per cent (106/777) of prisoners had serological evidence for blood-borne virus infection. No prisoner tested positive for all three viruses, and there was no co-infection with hepatitis B and HIV. However, 10 participants (1.3%) were found to be co-infected with hepatitis C and HIV. One (0.1%) was co-infected with hepatitis B and hepatitis C. The one factor identified as being significantly associated with co-infection was ever having shared injecting drug equipment.

Prison drug treatment and harm-reduction services

Participants were asked if they ever needed different types of drug treatment or harm reduction services while in prison. They were also asked whether those services were available to them (within a reasonable time frame) and, if available, whether they used those services. The different types of service were analysed by overall prison population, then by prison drug use category (see box) and by injecting drug use. Some of the main results are summarised below.

Overall treatment needs

The greatest proportion of respondents expressed a need for addiction counselling in prison (44%), while the smallest proportion expressed a need for alcohol detoxification (14%). Nineteen per cent of participants expressed a need for benzodiazepine detoxification, and the same proportion expressed a need for opiate detoxification.

The availability of specific drug treatments varied among participants who expressed a need for them. It ranged from low (22% for benzodiazepine detoxification) to high (73% for methadone maintenance treatment).

Overall, a high proportion of participants who needed a drug treatment service, and for whom it was available in prison, used the service, ranging from 95% for methadone maintenance to 78% for alcohol detoxification. The authors note that availability also varied across prisons (see below).

Need by prison drug use category

The need for services varied by prison drug use category. As might be expected, the expressed need was highest in the ‘very high’ drug use category prisons. The highest need in all prison categories was for addiction counselling, ranging from 56% in the ‘very high’ drug use category to 38% in the ‘low’ drug use category. The need for a more specific intervention, methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), ranged from 6% in the ‘low’ drug use category to 46% in the ‘very high’ drug use category.

An analysis of the reported availability of services (among those who needed them) by prison drug use category was also done. This showed a wide range of availability across categories. For example, in ‘very high’ drug use prisons 88% reported that MMT was available, compared to 49% in ‘medium’ drug use prisons. In the ‘very high’ drug use prisons, availability of drug-free wings or landings (28%) or drug free programmes (32%) was reported as low. Where these services were available there was high uptake, particularly in the ‘high’ and ‘very high’ drug use category prisons.

A sub-group of participants comprising those who had ever injected (IDUs) was analysed by prison drug use category. The expressed need for services was higher across all categories of prison drug use. The need was particularly high for addiction counselling (ranging from 62% to 82%) and drug-free treatment programme (ranging from 53% to 74%). The authors state that the results for the availability of services and high uptake of services for this group were similar to those in the general prison population as reported above.

_______________________________

Prison drug use category

The authors used a post-hoc hierarchical clustering model to categorise prisons based on prisoners’ self-reported use in the previous 12 months of the six drugs included in the EMCDDA ‘problem drug use’ definition.

By this method they identified four prison clusters based on levels of drug use, which they categorised as ‘low’, ‘medium’, ‘high’ and ‘very high’.

(For detailed description of the method used, see pp. 38–41 of the report.)

__________________________________

Overdose history

While over a quarter (27%) of all prisoners reported ever overdosing, the proportion among injecting drug users was much higher (58%). There were significant differences between genders, as women were more likely than men to report a history of overdose (44% compared to 26%). This difference was even more apparent for injecting drug users (80% compared to 55%). There were no significant differences between the age groups.

Almost a quarter (24%) of participants reported the need for information on overdose prevention, but only a quarter (25%) of those reported that it was available. However, where the information was available, almost all (88%) were able to access it.

As might be expected, the expressed need for this information was highest in the ‘very high’ drug use prison category (33%) the lowest in ‘low’ use category (17%). In spite of the high number who reported ever overdosing, participants reported limited availability of this information for those who needed it in the ‘high’ (27%) and ‘very high’ (25%) category prisons. However where this information was available, there was very good uptake, ranging from 75% in the ‘low’ use category to 100% in the ‘very high’ use category prisons.

Key messagesThe authors concluded that prisoner populations reflect a profile of social disadvantage and the verified reported rates for drug use8 and blood-borne viral infections are much higher than those in the general population.5-7 A considerable proportion of all prisoners reported ever overdosing, the proportion among injecting drug users was much higher. Where drug treatment is available, its uptake is very high.

Recommendations for drug treatment

- Prisoners on methadone treatment should be placed on a HSE clinic list or GP list to ensure that there is continuity of treatment on release from prison. This would reduce the risk of overdose and early relapse.9

- If a prisoner is engaging with counselling, where possible there should be continuity of this treatment on release in order to support transition out of prison and into the community.9

- A full range of drug treatment, encompassing an integrated clinical and psychological approach, should be available in all closed prisons.9

- There is a need for drug-free wings and drug-free areas not only for prisoners who do not use drugs but for those who wish to prevent relapse.9

- As the women’s prison was included in the ’very high drug use‘ category of prison, it is recommended that there be a specific strategy for the needs of women in order to improve their outcomes.9

Recommendation for overdose

- There is a need for a health promotion strategy in the prisons to include overdose prevention.

1. Drummond A, Codd M, Donnelly N (2014) Study on the prevalence of drug use,including intravenous drug use, and blood-borne viruses among the Irish prisoner population. Dublin: National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol. www.drugsandalcohol.ie/21750

2. Allwright S, Bradley F, Long J et al. (2000) Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV and risk factors in Irish prisoners: results of a national cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal, 321 (7253): 78–82.

3. Long J, Allwright S, Barry J et al. (2001) Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV and risk factors in entrants to Irish prisons: a national cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal, 323 (7323): 1209–1213.

4. Hannon F, Kelleher C and Friel S (2000) General healthcare study of the Irish prison population. Stationery Office, Dublin.

5. Thornton L, Murphy N, Jones L et al. (2012) Determination of the burden of hepatitis C virus infection in Ireland. Epidemiology and Infection, 140(8):1461–1468.

6. Health Protection Surveillance Centre (2011) Annual Report 2010. Dublin: Health Protection Surveillance Centre.

7. UNAIDS (2010) Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. Geneva: UN joint programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). www.drugsandalcohol.ie/14272

8. National Advisory Committee on Drugs (2011) Drug use in Ireland and Northern Ireland: first results from the 2010/2011 drug prevalence survey. Bulletin 1. Dublin: National Advisory Committee on Drugs & Public Health Information and Research Branch.

9. National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol (2014) Main findings and recommendations arising from the study on the prevalence of drug use, including intravenous drug use, and blood-borne viruses amongthe Irish prison population. Executive summary. Dublin: National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol. www.drugsandalcohol.ie/21750

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Needle (sharing / injecting)

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Communicable / infectious disease > Viral disease / infection

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Communicable / infectious disease > HIV

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Communicable / infectious disease > Hepatitis B

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Communicable / infectious disease > Hepatitis C (HCV)

G Health and disease > Disease by cause (Aetiology) > Communicable / infectious disease > Sexually transmitted infection / disease

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Health related issues > Health information and education > Communicable / infectious disease control

J Health care, prevention, harm reduction and treatment > Health care programme, service or facility > Prison-based health service

MM-MO Crime and law > Justice system > Correctional system and facility > Prison

T Demographic characteristics > Person who injects drugs (Intravenous / injecting)

T Demographic characteristics > Prison Inmate (prisoner)

Repository Staff Only: item control page