Mongan, Deirdre (2013) Alcohol: increasing price can reduce harm and contribute to revenue collection. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 44, Winter 2012, pp. 7-9.

| Preview | Title | Contact |

|---|---|---|

|

PDF (Drugnet Ireland, issue 44)

- Published Version

2MB |

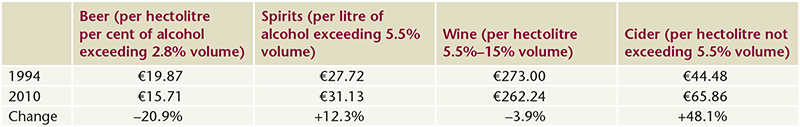

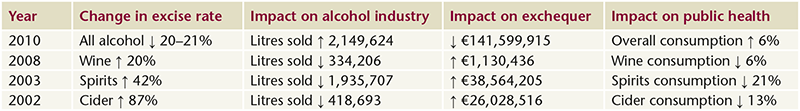

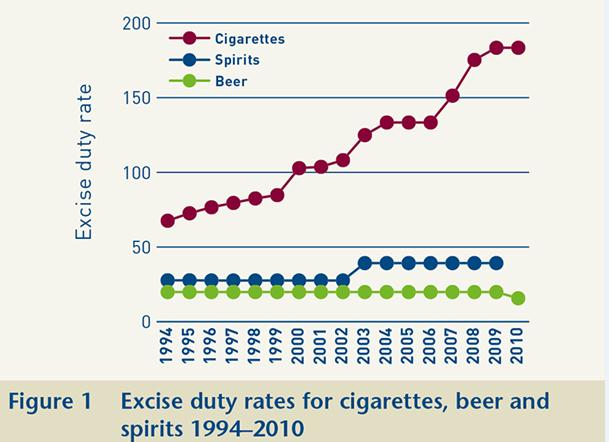

Alcohol is price sensitive – increasing the cost of alcohol reduces its consumption and decreasing the cost of alcohol increases its consumption. Price is therefore often used as a policy lever to reduce alcohol consumption and its related health and social harms. The two main pricing mechanisms that can be used to reduce consumption are taxation and minimum pricing. There are two types of taxes on alcohol in Ireland – excise duties, which vary with the different categories of alcoholic drink, and VAT, a uniform rate currently set at 23%. Excise duties are normally reviewed annually by the Minister for Finance in his Budget.

In general, a reduction in excise duty rates leads to increased alcohol sales, lower excise receipts and higher consumption, while an increase in excise duty rates leads to reduced alcohol sales, higher excise receipts and lower consumption. A recent illustration of the link between tax, price and consumption is provided by Finland, where in 2004 the government reduced alcohol excise duty by an average of 33% in order to reduce the number of cheap imports. The result was an immediate 10% increase in consumption and a 17% increase in alcohol-related mortality, equivalent to approximately eight additional alcohol-related deaths per week.2

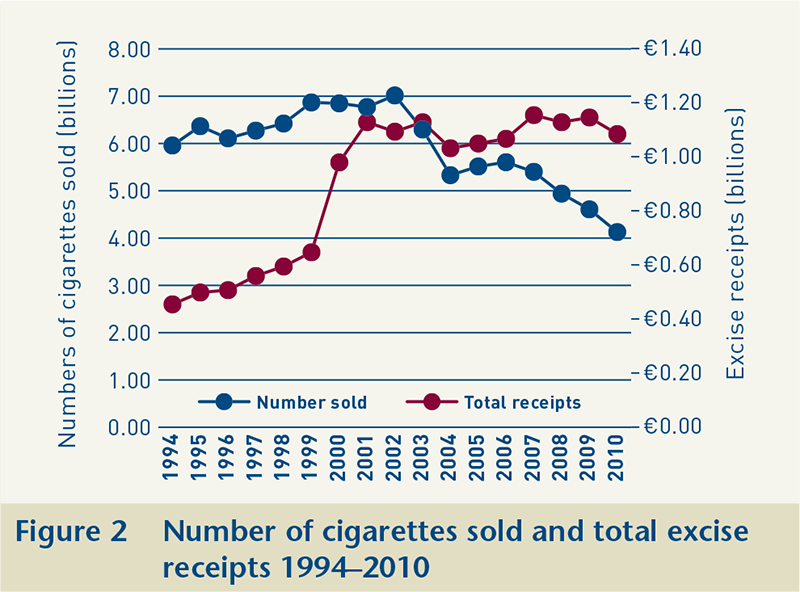

Coinciding with the excise duty rate increase on cigarettes, the number sold decreased by 31%. In addition to the positive public health benefits arising from a reduction in cigarette smoking, the excise duty receipts increased by 149% and amounted to €1.1 billion in 2010 (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Price regulation is the policy governments most commonly use to reduce alcohol consumption. It has a strong evidence base for reducing alcohol-related harm, although historically it has been used to increase revenue for government, rather than for social or public health reasons. Increasing excise duty rates increases the price of all alcohol regardless of whether it is sold in the on- or off-trade. However, an increase in tax may be absorbed by supermarkets and off-set by increasing the prices of other goods, and if alcohol is sold below cost price the retailer is entitled to a VAT refund on the difference between the cost price and the below-cost sale price, which deprives the state of revenue. Minimum pricing sets a price below which no alcohol beverage can be sold and which therefore cannot be undercut; it predominantly increases the price of the cheaper alcohol sold in supermarkets and mainly impacts harmful and younger drinkers. Excise duty and minimum pricing are not irreconcilable: a restoration of excise duty to the 2009 levels that existed prior to the last government’s 20% cut could have earned the government around €170 million in 2011.4 It is likely that a combination of taxation and minimum pricing will have the most beneficial effect on public health and will also provide increased revenue to the state at a time when harmful use of alcohol is responsible for 88 deaths each month and costs €3.7 billion annually. In 2009 the alcohol industry contributed €2.0 billion in the form of excise duty and VAT,5 leaving a net cost to the State of €1.7 billion in costs related to alcohol.

VA Geographic area > Europe > Ireland

G Health and disease > Substance use disorder > Alcohol use disorder

B Substances > Alcohol

A Substance use and dependence > Prevalence > Substance use behaviour > Alcohol consumption

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Economic policy

MP-MR Policy, planning, economics, work and social services > Economic aspects of substance use (cost / pricing)

Repository Staff Only: item control page